The stars are the jewels of the night,

and perchance surpass anything which day has to show.

— Henry David Thoreau

Open cluster M41, image credit: Anthony Ayiomamitis

The stars are the jewels of the night,

and perchance surpass anything which day has to show.

— Henry David Thoreau

Open cluster M41, image credit: Anthony Ayiomamitis

Are you tired of hearing the same weak atheist arguments over and over, but lack a definitive way to respond to them? Do you sense that they’re wrong, but have trouble articulating why? Chances are, you have a vague and passing familiarity with the philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, who demolished these arguments centuries ago; but to be an effective defender of your faith, what you need is a solid understanding of Aquinas’ Five Ways.

The following is a guest post by one of our readers, Russell, who has been studying Aquinas. After he left a comment about Aquinas’ Five Ways in another article, I requested that he write this overview. Once you familiarize yourself with the Five Ways, you’ll realize that they’re really just common sense—and excellent retorts to those atheists who demonstrate that their level of understanding doesn’t even rise to the level of common sense.

This is a quick overview of Aquinas’ most famous arguments, the Five Ways, for the existence of God. I’m not an expert on Aquinas, so any faults about his Ways are mine, not the good Doctor’s.

St. Thomas Aquinas was born in Italy, and lived from 1225 to 1274. Known as “Doctor Angelicus,” he was a great theologian, prolific writer, and the father of the Thomistic school of theology.

Aquinas combined Aristotelian dialectic with Christian theology. I know, doesn’t sound all that impressive. We can’t see how profound that was, because, like fish who can’t see the water in which they live, we can’t imagine a world without it. The combination of Athens and Jerusalem has been a cornerstone of Western Civilization, and his influence in this regard cannot be overstated.

Sadly, most modern ‘thinkers’ have no clue who Aquinas was, and therefore why their arguments against God are nothing more than the babbling of uneducated fools. They don’t realize Aquinas already dealt with the nattering nonsense that keeps trying to pass itself off as science and logic.

Aquinas’ Five Ways, or Quinque viae, are still standing, centuries later, as solid arguments for the existence of God. Not proofs of existence, like some keep saying, but arguments for the existence of God.

His Five Ways are:

You could spend a lifetime examining his arguments, but we’re not going to do that here. All I’m aiming for is a broad overview of the Big Five.

One core idea that Aquinas builds on is Aristotelian in nature: the difference between potentiality and actuality. The idea is, something can exist in one state or the other, say a rock on top a hill. The rock has the potential to roll down the hill, but it cannot do so on its own. If another force—say, a mover—pushes the rock, then it will actually roll down the hill.

The First Way

The first and more manifest way is the argument from motion. It is certain, and evident to our senses, that in the world some things are in motion. Now whatever is in motion is put in motion by another, for nothing can be in motion except it is in potentiality to that towards which it is in motion; whereas a thing moves inasmuch as it is in act. For motion is nothing else than the reduction of something from potentiality to actuality. But nothing can be reduced from potentiality to actuality, except by something in a state of actuality. Thus that which is actually hot, as fire, makes wood, which is potentially hot, to be actually hot, and thereby moves and changes it. Now it is not possible that the same thing should be at once in actuality and potentiality in the same respect, but only in different respects. For what is actually hot cannot simultaneously be potentially hot; but it is simultaneously potentially cold. It is therefore impossible that in the same respect and in the same way a thing should be both mover and moved, i.e. that it should move itself. Therefore, whatever is in motion must be put in motion by another. If that by which it is put in motion be itself put in motion, then this also must needs be put in motion by another, and that by another again. But this cannot go on to infinity, because then there would be no first mover, and, consequently, no other mover; seeing that subsequent movers move only inasmuch as they are put in motion by the first mover; as the staff moves only because it is put in motion by the hand. Therefore it is necessary to arrive at a first mover, put in motion by no other; and this everyone understands to be God.[1]

Things do move. We see them moving. Something has to move the thing that’s moving. Potentiality is only moved by actuality. Something can’t exist potentially moving and actually moving. So a potential depends on an actual to change it to an actual. There has to be something that does not need to be moved, that moves all things, and that is God.

This isn’t what most people think it is—this is not an argument for a beginning of a temporal series. The Unmoved Mover in this case is above the lower elements of the set. Aquinas jumps categories, from things that are contingent to a non-contingent entity. There has to be a change in categories because the non-contingent entity is fundamentally different than contingent things. Aquinas will make use of this idea again. And because this is only talking about contingent things, Aquinas says only contingent things have a start to their movement.

The Second Way

The second way is from the nature of the efficient cause. In the world of sense we find there is an order of efficient causes. There is no case known (neither is it, indeed, possible) in which a thing is found to be the efficient cause of itself; for so it would be prior to itself, which is impossible. Now in efficient causes it is not possible to go on to infinity, because in all efficient causes following in order, the first is the cause of the intermediate cause, and the intermediate is the cause of the ultimate cause, whether the intermediate cause be several, or only one. Now to take away the cause is to take away the effect. Therefore, if there be no first cause among efficient causes, there will be no ultimate, nor any intermediate cause. But if in efficient causes it is possible to go on to infinity, there will be no first efficient cause, neither will there be an ultimate effect, nor any intermediate efficient causes; all of which is plainly false. Therefore it is necessary to admit a first efficient cause, to which everyone gives the name of God.[1]

In some ways this is another angle to his First Way. Nothing can cause itself, for it would have to pre-exist itself to do so. So anything caused has to have a cause. You can’t have an infinite number of causes, because something along the way has to change the potential causes into actual caused. There might be more than one intermediate causes, but they, too, can’t stretch into an infinite series for the same reason. So there has to be another category above causes and caused, an Uncaused Cause, which we call God.

How long of a paint brush would you need to get it to paint by itself? A meter? 100 meters? An infinite length? The answer is, there is no length that will change the potential nature of the brush to an actually painting brush. It will require a mover, a cause, to do so.

Movement and cause are the same: that which is contingent has to rely on an non-contingent entity to become actual and caused. Again, this isn’t a temporal series. It can apply to those, but the underlying requirement is the Uncaused Cause, the Unmoved Mover, which is in a different category than contingent things.

The Third Way

The third way is taken from possibility and necessity, and runs thus. We find in nature things that are possible to be and not to be, since they are found to be generated, and to corrupt, and consequently, they are possible to be and not to be. But it is impossible for these always to exist, for that which is possible not to be at some time is not. Therefore, if everything is possible not to be, then at one time there could have been nothing in existence. Now if this were true, even now there would be nothing in existence, because that which does not exist only begins to exist by something already existing. Therefore, if at one time nothing was in existence, it would have been impossible for anything to have begun to exist; and thus even now nothing would be in existence – which is absurd. Therefore, not all beings are merely possible, but there must exist something the existence of which is necessary. But every necessary thing either has its necessity caused by another, or not. Now it is impossible to go on to infinity in necessary things which have their necessity caused by another, as has been already proved in regard to efficient causes. Therefore we cannot but postulate the existence of some being having of itself its own necessity, and not receiving it from another, but rather causing in others their necessity. This all men speak of as God.[1]

The Third Way is another angle of the first two, but Aquinas really brings out the need for a non-contingent entity.

These first three ways are profound enough to answer the blathering ninnies that run about saying stupid things like, “If everything has a cause, then what caused God?” and “What if the Universe is of infinite time, Bible boy? What then?”

The first question—what caused God—shows the utter lack of education possessed by many of those with degrees. Aquinas doesn’t argue that everything has a cause, but that everything contingent has a cause. If you are talking with someone who makes the argument that God should have a cause, you should kindly point out that no serious philosopher has made that argument, especially not Aquinas, not Aristotle, and not even William Lane Craig.

Here’s a bit of advice for Christians defending against such an argument. If the person persists in maintaining that’s the argument, he’s not arguing from good faith, he’s intellectually dishonest and you may treat him as such. Dialectic arguments should only be used to explode his pseudo-dialectic mutterings. Use rhetoric to strike against his emotions. Stick to the truth. You’ll do fine. If he accepts your correction, you could end up having a delightful discussion with him.

The second question—what if the universe is infinite in time—isn’t quite as cut and dried. Aquinas makes an argument for a single act of creation, but he also argues such an event isn’t needed. The tricky part is understanding that Aquinas’ argument for God is not one of a temporal series in and of itself, but that God, the Unmoved Mover, the Uncaused Cause, the Necessary Being, is fundamentally different than anything that isn’t Him. God is a different category altogether. If the Universe has begun to exist, then it there needs a Cause that is Uncaused. I know, dead horse. And for everything in the Universe, there needs be a Necessary Being to uphold all existence, because if something can not exist at one point, it lacks the ability to self-exists.

If the Universe has always existed, or even if there’s an infinite number of Universes, then there needs be a Necessary Being to uphold all existence. It doesn’t matter if there is a beginning or not to the Universe, everything contingent needs to be upheld moment to moment by the Necessary Being.

“Fine, but what about a quantum field fluctuations?” Same answer.

See, the problem is at this point, the person arguing against God while trying to use science is barking up the wrong category. God’s involvement is metaphysical, above nature, also know as supernatural. Using contingent factoids cannot prove or disprove arguments from a metaphysical category.

The guy arguing against God needs to engage the actual arguments made by Aquinas at the same level in order to be rational. Anything less is dishonest.

The Fourth Way

The fourth way is taken from the gradation to be found in things. Among beings there are some more and some less good, true, noble and the like. But ‘more’ and ‘less’ are predicated of different things, according as they resemble in their different ways something which is the maximum, as a thing is said to be hotter according as it more nearly resembles that which is hottest; so that there is something which is truest, something best, something noblest and, consequently, something which is uttermost being; for those things that are greatest in truth are greatest in being, as it is written in Metaph. ii. Now the maximum in any genus is the cause of all in that genus; as fire, which is the maximum heat, is the cause of all hot things. Therefore there must also be something which is to all beings the cause of their being, goodness, and every other perfection; and this we call God.[1]

Like Aquinas’ other Ways, this is just a summary of his arguments. He spends hundreds of pages explaining why God has to be Good and not just anything. This is not a quantitative argument about sums and magnitudes, but one of transcendental perfection. To treat this as the extent of his argument is either ignorant or dishonest.

For example:

That’s an argument? You might as well say, people vary in smelliness but we can make the comparison only by reference to a perfect maximum of conceivable smelliness. Therefore there must exist a pre-eminently peerless stinker, and we call him God. Or substitute any dimension of comparison you like, and derive an equivalently fatuous conclusion. — Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion

Q.E.D.

The Fifth Way

The fifth way is taken from the governance of the world. We see that things which lack intelligence, such as natural bodies, act for an end, and this is evident from their acting always, or nearly always, in the same way, so as to obtain the best result. Hence it is plain that not fortuitously, but designedly, do they achieve their end. Now whatever lacks intelligence cannot move towards an end, unless it be directed by some being endowed with knowledge and intelligence; as the arrow is shot to its mark by the archer. Therefore some intelligent being exists by whom all natural things are directed to their end; and this being we call God.[1]

This is just common sense, which explains why most learned men of our age have no idea what point Aquinas is making here. That which lacks intelligence cannot have a purpose. Unintelligent thing act according to laws set for them. Intelligence precedes laws. So, that which has set the laws by which all things are governed we call God.

Since we don’t know for certain what the physical laws were like during the first blip after the Big Bang, we can’t describe how things worked. But, again, God is above that, He had laid down governance for those initial conditions as much as He did for the material Universe after. All things operate according to His will.

The implications should be clear, no matter what law is discovered by man’s questing, it cannot supersede God. There is no God of the gaps for Aquinas—God is above and below all.

To summarize, Aquinas argues for some Being that is above everything as the First Cause, the Unmoved Mover, and is the fundamental source of everything, the Necessary Being. He is the Alpha and the Omega, whom men call God. He exists in a different category than everything else in the Universe, and is not just one entity among many.

Every time someone makes an argument against God and either doesn’t address Aquinas or does so incorrectly, despite being corrected, you know they are not arguing honestly. No fact of the physical universe can prove or disprove God. No law, no factoid, no wild-eyed claims of quantum field fluctuations can address the wrong category.

So why aren’t these Ways considered proofs? Aquinas set out to defend belief in God as being philosophically rational at a metaphysical level, not something empirically provable, by merging Athenian logic and Jerusalem belief.

In this benighted age, where Science über alles is the mode de jour of all right-thinking people, this is nigh well unconceivable. It’s claimed that science encompasses all knowledge, including metaphysics, which is an absurd position to take, since that means science also includes astrology and the rules to croquet.

The Five Ways aren’t arguments for Jesus being the Son of God or that the Bible is the Word of God, but that there are rational reasons for accepting the existence of a Supreme Being, whom men call God.

This was just a quick flyby at 30,000 feet. Aquinas was a prolific writer, and he explores these ideas further in many books and hundreds and hundreds of pages.

If this has piqued your interest, I suggest checking out Professor Edward Feser’s blog. Professor Feser has a gift for explaining Aquinas clearly, as well as many philosophical arguments, both the pros and cons. I also recommend Aristotle’s Metaphysics, and, of course, the Summa Theologica.

[1] Wikipedia : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quinque_viae

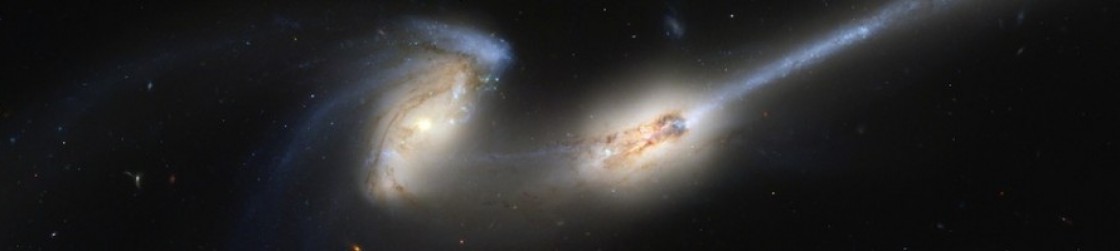

Here is your weekly reminder of Psalm 19 — colliding galaxies, Arp 274.

Galaxy collisions are a testament to the strange way in which space is scaled. The universe is a relatively crowded place on the galactic scale, which is why these collisions are fairly common. But when galaxies crash into each other, the stars in them are so far apart from each other that the stars themselves usually don’t collide.

Think of it this way. If you were to draw a 1 cm dot that represented the Sun, the nearest star to the Sun (Alpha Centauri, ~4 light-years away) would be a slightly larger dot about 400 km away. That’s how much space there is between the stars.

Now, if you were to draw a 1 cm dot that represented the Milky Way Galaxy, the nearest galaxy to ours (Andromeda, ~2.5 million light-years away) would only be 25 cm away.

That’s why galaxies often collide, but stars usually don’t. However, the gas and dust that is inside galaxies does collide, and this leads to a brief period of intense star formation as the galaxies gravitationally tear each other apart. Once this violent dance settles down, a newly formed galaxy remains.

Galaxy collisions take hundreds of millions of years to play out, so what we’re seeing with images like the one above are cosmic snapshots of collisions. Astrophysicists use supercomputer simulations to hugely speed up the process and explore what a full collision would look like.

Image credit: NASA, ESA, M. Livio (STScI) and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA).

There’s not a lot going on in the November sky, but here are couple events you and your family can enjoy, with or without binoculars.

November 5,6: Taurids Meteor Shower. Meteor showers occur when the Earth moves through a cloud of debris left behind by a celestial object, like a comet. The Taurids are unusual in that they are debris from two objects: Asteroid 2004 TG10 and Comet 2P Encke. The meteors will appear to radiate from the constellation Taurus. As meteor showers go, this one is wimpy, with a modest 5-10 meteors per hour at its peak. The shower runs every year from September 7 to December 10, but will peak after midnight in the early morning of the 6th.

November 17,18: Leonids Meteor Shower. The Leonids are debris from Comet Tempel-Tuttle, and appear to radiate from the constellation Leo. As meteor showers go, this one is average with 15 meteors per hour at its peak. The shower runs every year from November 6th to November 30th, but will peak after midnight in the early morning of the 18th.

A recent pop news article claimed physicists have proved God didn’t create the universe. In response, I explained why you can’t trust the pop media to report on science accurately. In a follow-up post, I discussed why the universe isn’t “nothing,” as the article implied. In this, the third part, we’ll talk about what the Bible says about the creation of the universe and compare this with the current state of scientific thinking.

Let’s first summarize the problem as presented in the pop news article:

The supposed biblical claim: God created the universe from absolute nothing (creatio ex nihilo). Only God could create something from absolute nothing.

The atheist counterclaim: Physicists have discovered a way to create a universe from nothing using only the laws of physics. Therefore, God is irrelevant.

I’ve already explained why the atheist claim is bogus. But is creatio ex nihilo what the Bible says? It’s unclear, because there is nothing in scripture that explicitly says this. Those who believe creatio ex nihilo infer it from Genesis 1:1: In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. It’s not an unreasonable inference—the Hebrew word for “create” means to bring something into existence that did not exist before—and it is probably for this reason that the great biblical commentator Nahmanides believed the universe was brought forth by God “from total and absolute nothing.” From my reading of Nahmanides (and my non-expertise in theology), the total and absolute nothing refers to something corporeal. More on this in a moment.

When dealing with argumentative atheists who want to debate science and God, what matters most is not whether science lines up with their particular ideas about God, but whether science is consistent with what we know from scripture. You have to be persistent about this, because atheists almost always present their arguments against a God that resembles nothing like the God of the Bible:

Asked if the remarkable findings and the convincing if complex solution removed the need for a God figure to kick start the universe Dr Mir said: “If by God you mean a supernatural super man who breaks his own laws then yes he’s done for, you just don’t need him.”

I doubt this is the exact question posed to Dr. Mir; and I believe the atheist we’re dealing with is not the physicist, but the reporter and/or his editor. Nevertheless, my interpretation of Mir’s response is, now that we have a plausible physical model for how the universe could arise from nothing but physical laws, we do not need the sort of God who waves his arms and magically conjures up a universe from nothing. In other words, the theory knocks down a strawman God. But it also supports the biblical God who operates in a way that we can relate to on at least a rudimentary level.

Have you ever watched a skilled magician performing tricks? Most people find it enjoyable to watch someone perform something that seems impossible. But it’s only fun, because everyone except for really little kids understands that the tricks are just illusions and the magician isn’t really defying the laws of nature. If we genuinely believed he was defying the laws of nature, the magic show would be more horrifying than entertaining*.

And yet, for reasons I don’t quite understand, a lot of people—including believers—regard God as the ultimate magician who really is defying the laws of nature. Personally, I find this notion of God repellant, because it contradicts what the Bible tells us about his character—he is knowable through nature, he is consistent, and he is reliable. But we needn’t worry, because the biblical account of the creation of the universe doesn’t describe something magical, it describes something miraculous.

It is tempting to think of magical and miraculous as synonymous, but there’s an important distinction between the two. For the purpose of this argument, magical refers to something that lacks a knowable mechanism, something that defies the laws of nature or does the impossible. Contrary to popular misconception, miraculous means none of those things. Rather, a miracle is something that is accomplished through divinely supernatural means; in other words, something that is accomplished by God through means that exist beyond the universe. As Israeli physicist and theologian, Gerald Schroeder, points out, this is exactly what modern science implies for the creation of the universe.

Prof. Mir – who also works on the Large Hardron (sic) Collider at CERN in Switzerland – further explained that by “nothing” he only meant absence of energy, and not the absence of laws of physics.

Schroeder says this is what Genesis has been telling us all along. In his book, The Science of God, he provides what he considers to be the most faithful translation of Genesis 1:1, which is known as the Jerusalem translation: With wisdom as the first cause, God created the universe. In other words, Genesis implies the laws of physics predate the universe, just as physicists claim. It is the supernaturally existing laws of physics—wisdom, the first cause—God uses to create the universe.

Let’s summarize what we’ve discussed:

Logically, we know the universe can’t create itself; it requires something above and beyond. This is what the Bible has been saying all along, and science is finally catching up.

—–

* If you don’t believe me, watch a movie called The Prestige. Even though the ultimate trick in the movie isn’t strictly magic—in the sense that it breaks no laws of nature—the magician goes well beyond simple illusion, and it’s pretty disturbing.

Image credit: ESO.

Here is your weekly reminder of Psalm 19 — Saturn’s moon, Enceladus.

Enceladus is the sixth-largest of Saturn’s 62 moons. At 500 km diameter, it is dwarfed by Saturn’s largest moon, Titan (5,100 km) and Earth’s Moon (3,500 km). It was discovered in the late 18th century by the German-English astronomer, William Herschel, whose son, John, named it. Not much was known about Enceladus until the Voyager missions studied the moon in the 1980s. The Cassini mission followed in 2005 to study Saturn and its moons in greater detail. The above image was taken during this latest mission.

The surface of Enceladus is comprised of clean ice (as opposed to “dirty” ice, which contains rock, dust, and organic compounds) that reflects most of the sunlight that reaches it. Enceladus has an active surface, with over 100 geysers spewing water vapor into the rings of Saturn. Last year, Cassini found evidence of a subsurface ocean beneath the icy surface. The Cassini spacecraft is scheduled to fly through one of Enceladus’ geyser plumes in the hope that it will reveal the chemical makeup of its liquid ocean.

Image credit: NASA/JPL.

I’ll never forget my first experience with the media. When I was an undergrad, a reporter for the local newspaper came to our little university to cover a major event — our physics club was hosting a public lecture and Q&A event with an Apollo 13 engineer. I eagerly read the newspaper the next day to see how the reporter had covered the event, and was struck by how much he’d gotten wrong. The reporter had attended the event, taken pages of notes, and interviewed a few of us physics students, and he still managed to bungle many of the facts.

A few years later, I was interviewed by the Discovery Channel’s printed news outlet for an article about an extremely massive black hole. Unlike the newspaper reporter, this one managed to get all the scientific facts right; however, I was taken aback by the article. The quotes that were attributed to me were not verbatim. I realized the reporter had taken our 20-minute interview and condensed it into two quotes she had written herself that captured the essence of everything I’d said. Perhaps this is standard journalistic practice, but in my opinion, when you put quotation marks around something, it ought to represent exactly what someone said.

I’ve had other experiences with the media, ranging from mild to ludicrous, where I recognized that the media were either inept with the facts or deliberately misrepresenting them. After the first couple of times, I realized I was criticizing how the media were reporting events on which I had expertise, but was blithely accepting their reporting on events about which I knew little. The late popular author, Michael Crichton, described this as the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect:

Media carries with it a credibility that is totally undeserved. You have all experienced this, in what I call the Murray Gell-Mann Amnesia effect. (I refer to it by this name because I once discussed it with [Nobel laureate physicist] Murray Gell-Mann, and by dropping a famous name I imply greater importance to myself, and to the effect, than it would otherwise have.)

Briefly stated, the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect works as follows. You open the newspaper to an article on some subject you know well. In Murray’s case, physics. In mine, show business. You read the article and see the journalist has absolutely no understanding of either the facts or the issues. Often, the article is so wrong it actually presents the story backward–reversing cause and effect. I call these the “wet streets cause rain” stories. Paper’s full of them.

In any case, you read with exasperation or amusement the multiple errors in a story–and then turn the page to national or international affairs, and read with renewed interest as if the rest of the newspaper was somehow more accurate about far-off Palestine than it was about the story you just read. You turn the page, and forget what you know.

That is the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect. I’d point out it does not operate in other arenas of life. In ordinary life, if somebody consistently exaggerates or lies to you, you soon discount everything they say. In court, there is the legal doctrine offalsus in uno, falsus in omnibus, which means untruthful in one part, untruthful in all.

But when it comes to the media, we believe against evidence that it is probably worth our time to read other parts of the paper. When, in fact, it almost certainly isn’t. The only possible explanation for our behavior is amnesia.

Readers have a tendency to forget that the media are not coldly objective entities or benignly omniscient beings, but people. And to be blunt, people are crappy. What I mean is, people are rarely objective, because we all suffer from at least some of these things:

While some of us are better at recognizing and minimizing these things than others, it’s impossible to eliminate them entirely. This means everything you consume from the media — including anything I write on this blog — has been run through one or more of these filters. This is why your default position with the media should be skepticism. It’s annoying and tiresome, but it means you can’t just be a passive consumer of media — you have to be diligent and judicious in deciding what’s truth and what isn’t.

Last time, we learned you can’t trust the pop media to report on science accurately. The article in question concerned physicists ‘PROVING’ God DIDN’T create the universe. The headline was, of course, a total lie.

Today we’ll discuss why the article’s claim was bogus. In the third part of this series, we’ll talk about why none of the science involved is a problem for biblical belief, anyway.

The science in the article involves two things: cosmic inflation and something called doubly special relativity. It’s really just an interesting bit of mathematics to figure out what’s going on in the early universe, since plain old relativity tells us nothing.

Our current understanding of physics allows us to describe the history of the universe back to an early time, when the universe was small in scale; but it doesn’t allow us to describe the universe at the very beginning, when things were extremely small in scale. That irritates physicists, who want to know exactly how the universe began. But what can be done about it?

Since the universe probably began at the quantum scale, we need a better understanding of relativity at the quantum level. It turns out to be a difficult thing to do. But every now and then a bunch of physicists, like the professors at the Canadian university, find a mathematical solution that seems to work.

So far, this isn’t anything terribly controversial, right?

And the findings are so conclusive they even challenge the need for religion, or at least an omnipotent creator – the basis of all world religions.

Oh.

Only that doesn’t seem to be what the physicists were intending at all. I emailed one of them to ask about the news article, and he seemed dismayed by the way the discussion had turned from science to God.

So, why the insanely provocative headline and the silly claim in the article? As we discussed last time, it generates a lot of clicks and more ad revenue. What better way to provoke people than to say that scientists have given God the heave-ho?

Now, only an utterly stupid person would claim there’s such a thing as proof of God’s nonexistence, and since most people (excluding tabloid editors) aren’t that stupid, the next best thing is to make God irrelevant. That’s why we have articles claiming the universe never had a beginning, implying that God isn’t necessary to create it.

Another way to make God irrelevant is to say there is nothing that needs explaining in the first place. The prevailing belief in Christianity is that God created the universe from nothing, what’s referred to as creatio ex nihilo. Whether or not that’s precisely what the Bible says, we’ll discuss next time. But for now, the point is, a universe from nothing requires the miraculous intervention of God. Or does it?

According to the extraordinary findings, the question is irrelevant because the universe STILL is nothing. … the negative gravitational energy of the universe and the positive matter energy of the universe basically balanced out and created a zero sum.

Stephen Hawking has used this argument before, and there has yet to be a word invented to describe how silly it is. It’s like your child asking you where money comes from, and you answer by claiming that because your income balances your debts, there is no money. Most children would recognize that answer as a pathetic cop-out.

Nevertheless, I’ve heard quite a few materialist atheists parrot it as a rebuttal to the idea that God is necessary to explain a universe from nothing.

It’s kind of astounding to behold a supposedly rational materialist so pretzel-bent by his philosophy that he denies the existence of the ONE THING he’s supposed to believe exists. I don’t much respect the philosophy of Ayn Rand anymore, but one thing I do respect about Objectivism is its first tenet: existence exists. As a teenager enamored with Rand’s philosophy, I couldn’t understand the need to state this, but apparently there are people who believe the universe is effectively nothing. Hence, the need to establish the existence of existence as the beginning of all materialist wisdom.

Anyway, what’s going on here is that Hawking and others like him are playing fast and loose with the definition of nothing. The great mathematician Gottfried Leibniz once asked, “Why is there something rather than nothing?” He meant, why is there anything at all (the universe) rather than nothing at all? By nothing, he meant NOTHING. No space, no matter, no positive or negative energy. Zilch. Nada. Zip. The complete and total absence of anything. Yet, quite clearly, Hawking and the Canadian physicists are spending a lot of time studying something—the universe—therefore, “How can it exist?” requires a better answer than the one we’re getting.

Next time, we’ll conclude this discussion and talk about how these new findings are, in fact, consistent with biblical wisdom.

Last week, an atheist acquaintance of mine showed me this article, to which she added the triumphant notation “BAM!” as though science had finally pulled the plug on God.

However, as I proceeded to explain to her, the article merely shows: a) she doesn’t understand how science and logic work; b) pop media reporters don’t understand how science and logic work; and c) you can’t trust the pop media to report scientific news accurately.

In a follow-up article, I’ll explain why the reporter’s claim is wrong. For now, I’ll talk about how you can tell right away that this article is not trustworthy.

In parsing this turkey of an article, a few things immediately jumped out. First of all, the headline is ludicrous. No respectable scientist would ever say anything like that. You can’t prove God didn’t create the universe unless you prove that something else did. Second, the ridiculous Daily Express article doesn’t really support that claim. Third, if you read the actual scientific paper, it makes no such claim whatsoever. In fact, I contacted one of the paper’s authors, a scientist at the University of Waterloo who was interviewed by the Express reporter, and he was surprised and dismayed by the way his work was misrepresented. He said he was expecting an article on inflation and relativity, not God.

This is part of a pattern I’ve noticed developing in the pop media. Prior to this, we had another declaration that the universe didn’t have a beginning (implication: Genesis 1:1 is irrelevant). I’m pretty sure what reporters are doing is combing through the arXiv eprint service for theoretical cosmology papers that have something to do with the origin of the universe, calling the authors for a quickie interview, and then shoe-horning the information into a narrative that the universe has no beginning, God is irrelevant, etc.

I keep telling you, my dear readers, atheists hate the big bang. They know exactly what it means — someone or something created the universe, and they cannot rule out God.

Does this mean you can’t trust anything the media say about science? No. There are good science reporters out there, you just have to be judicious in deciding what’s trustworthy and what’s not. I had a good experience being interviewed by a reporter from Discovery News about black holes a few years ago; it was clear she knew her stuff, and she wrote a good article. But then, unlike the Daily Express, which is a tabloid, Discovery News is a respectable science-oriented publication. But even then you have to be careful.

So, how do you know when to be skeptical? It can be hard to know, especially if you’re not a scientist who knows what to look for. I sometimes get duped by misleading articles when it’s about something outside of my area of expertise. But there are a few reliable tells. You should be skeptical any time you’re reading a science article that includes:

Keep in mind that editors have the final say over headlines and even the content of the article. There’s a good chance the reporter of the Express article did not choose that insanely provocative headline. A newspaper makes money through advertising, which means it needs to generate a lot of clicks from readers. The more grabby the headline, the more likely it will generate clicks. Once you click, it doesn’t matter to the bottom-line people at the newspaper if the article doesn’t entirely square with the outrageous headline.

Also, not everything that has an agenda or is shocking or revolutionary is necessarily going to be untrue. After two millennia of believing the universe was eternal, the news that the universe had a beginning was shocking and revolutionary, and required a lot of people to rethink their worldviews. Einstein’s relativity was pretty revolutionary. Quantum mechanics was revolutionary and just downright weird. But here’s the kicker — they were all supported by an abundance of very good evidence that continues to mount to this day. Also, two of these discoveries (quantum mechanics and relativity) have led to practical technological breakthroughs that have improved everyday life, like modern electronics and GPS.

In my next post, I’ll discuss the specifics of why the Express article was wrong, and how you can spot similar bad reporting in the future.

Here is your weekly reminder of Psalm 19 — our galactic home, the Milky Way.

This graceful arch across the sky is our home, as seen from within the Galaxy itself.

Have you ever wondered why it’s called the Milky Way? The ancient Greeks called it the “milky circle,” because they thought it looked like milk spilled across the sky. (The Greek word for “milky” is galaxias, which makes the name Milky Way Galaxy a little tautological.)

The Milky Way is a spiral galaxy, about 100,000 – 150,000 light-years across. It contains an estimated 200-400 billion stars, including our Sun. The Solar System is located about 30,000 light-years away from the center of the galaxy at the edge of the Orion arm (see image below). Incidentally, did you know there are stars between the arms in a spiral galaxy? Quite a few actually, but many of them are not visible because they are dimmer than the very luminous massive stars that tend to bunch up in the arms.

The Milky Way has a supermassive black hole in its center, just like every other galaxy that’s been observed. It weighs in at about 4 million times the mass of the Sun, which may sound like a lot, but is kind of “meh” as far as supermassive black holes go (some of these giant black holes tip the cosmic scales at 10 billion times the mass of the Sun). If you wanted to look in the sky in the direction of this black hole, called Sagittarius A*, you would look at the Milky Way in the direction of the constellation Sagittarius. You wouldn’t see anything that suggests a black hole, especially because it’s smaller in size than Mercury’s orbit around the Sun, but it’s sort of fascinating to know that it’s there nevertheless.

Fraser Cain explains what we’re actually looking at when we observe the Milky Way in the sky:

Milky Way image credit: Steve Jurvetson. Milky Way schematic credit: Sky & Telescope magazine.