Miracles are part of Christian tradition that are often ridiculed by atheists. The claim is that God or one of God’s agents does the impossible, and impossible things never happen, because they defy the laws of nature, so why do you believe in something as nonsensical as miracles?

But is that really what all miracles are — defying the laws of nature and doing the impossible?

Before we get into the physics, let’s first go to scripture to see how miracles are defined. (Generally speaking, in any argument with atheists over something in scripture, the first thing you should do is carefully study the relevant passages to see what the actual claim is. Atheists almost always get it wrong.)

There are two Hebrew words translated as ‘miracle’ in the Old Testament. They are

- oth: this word refers to a sign. The purpose of this sort of miracle is to draw people’s attention to God. (e.g. Exodus 12:13)

- mopheth: this word refers to a wonder and is often used together with oth (signs and wonders). The purpose of this sort of miracle is to display God’s power. (e.g. Exodus 7:3)

The Greek counterparts in the New Testament are

- semeion: this word refers to a sign, and is used to describe acts that are evidence of divine authority, usually something that goes against the usual course of nature (e.g. John 2:11)

- teras: this word refers to a wonder, and is used to describe something that causes a person to marvel (e.g. Acts 2:22)

There are two additional words used for miracle in the New Testament:

- dunamis: this word refers to an act that is supernatural in origin (e.g. Mark 6:2)

- ergon: this word means “work,” as in the works of Jesus (e.g. Matthew 11:2) (interestingly, ergon is the Greek word from which the unit of energy, erg, is derived)

Is it possible to square some miracles with the laws of nature without detracting from their wondrousness? I believe the answer is yes, based on two branches of physics: thermodynamics and quantum mechanics. In this first part, I’ll discuss miracles from the perspective of thermodynamics, the branch of physics that deals with heat, energy, and work.

What follows is more properly described as statistical mechanics, or statistical thermodynamics, but you don’t need to get hung up terms. This field of study deals with predictions about the behavior of systems with enormous numbers of particles. These numbers are so huge that no one could be absolutely certain about any predictions, but this is where statistics come to the rescue. You can make statistical predictions about systems of particles, and, as you’ll see, the more particles you’re dealing with, the more accurate the predictions become. And, interestingly, this is precisely what permits miracles that do not violate the laws of nature.

The laws of nature permit a lot more than most people realize. In our everyday lives, we don’t usually define common sense expectations in terms of probabilities, but that’s often precisely what common sense is. In thermodynamics, that which constitutes our everyday expectation in any given situation is what’s referred to as the most probable state of a system.

To see what I mean, let’s consider a room with air in it, and imagine that we divide the room into two equal parts. We’ll also imagine this room and the air molecules comprise a closed system: the room has been effectively sealed off with its doors and windows closed for several hours, with no energy or air added to or removed from it. This means the room has had time for the air particles to jostle around and distribute themselves randomly. What we expect when we walk into the room is that the air molecules will be relatively evenly distributed throughout the room with approximately the same number of molecules on either side. What we don’t expect is that all of the air molecules will be on one side of the room with a vacuum on the other side. Most of you probably couldn’t explain why you’d be astonished to find all of the air on just one side of the room — you intuitively sense that this would be extremely odd — but there is a sound reason for this expectation that is rooted in probability.

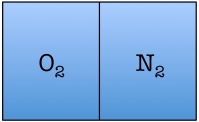

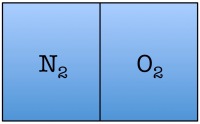

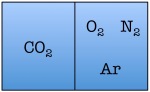

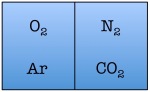

Let’s construct what scientists call a toy model, which is a very simplified example of a situation you wish to study, in order to understand the fundamentals. Our toy model consists of a room divided in half with only two air molecules in it, an oxygen molecule and a nitrogen molecule. Here are the possible arrangements of these molecules:

Each possible arrangement is called a “state” of the room. We see that there are four possible states for the room. There are two states in which the air molecules are distributed evenly in the room, and two in which both of the air molecules are on one side of the room. The probability of finding a room in a state in which both molecules are on one side of the room is 2 out of 4, or 50%.

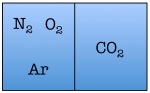

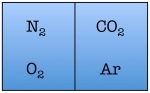

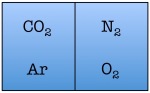

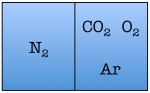

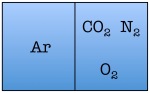

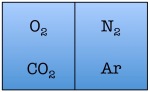

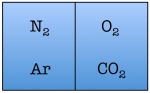

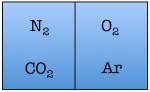

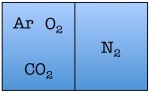

Easy enough. But things start to change quickly the more particles we add. Let’s see what happens when we double the number of molecules to four — one nitrogen, one oxygen, one argon, and one carbon dioxide.

As you can see, there are a total of 16 possible states for the room. Again, there are only two states in which the air molecules are on one side of the room, but now there are many more total possible states than before. The probability of all four molecules spontaneously arranging themselves on one side of the room is 2 out of 16, or 12.5%. This is a lot less probable than in the previous example, but not so low that you would be astonished to find all of the air molecules on one side of the room.

Based on this toy model, we can write the mathematical expression for the total number of possible arrangements of air molecules in a two-sided room as

total # of states = (2 sides of the room)# of molecules

or

2N

That’s 2 raised to the power of the number of molecules. For the two-molecule example, that’s 22 = 4, and for the four-molecule example, that’s 24 = 16.

Let’s consider a room with N = 100 air molecules in it, and calculate the probability of finding all of the molecules on one side of the room:

total # of permutations = 2100 = 1030

Even with a paltry 100 air molecules in the room, the probability of finding them all on one side of the room is a minuscule 2 out of 1030 possible permutations. Let’s put this in perspective. If the air molecules randomly redistributed themselves every second, you’d have to wait a trillion lifetimes of the universe before you’d have a reasonable expectation of finding all 100 air molecules on one side of the room.

Let’s now consider a typical room, which has N = 1027 air molecules in it. That number is a 1 with 27 zeroes after it

1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000

or a billion billion billion.

The total number of possible arrangements of the air molecules in a room divided into two equal parts is

2N = 21027

or 2 raised to the power of a billion billion billion. It’s an absurdly large number.

There are still only two possible ways for all of the air molecules to be on one side of the room or the other, so the probability of finding a room in a state in which all of the air molecules are, by random chance, on one side of the room or the other is 2 out of 21027. To say that this is an extremely improbable state is beyond understatement.

In fact, by any reasonable definition, we can say that it’s effectively impossible for the air molecules in a room to spontaneously arrange themselves to be on just one side of the room. But notice that it’s not strictly impossible. The probability of finding the air molecules on one side of the room by chance is extremely, extremely low, so low that we would never expect it to happen in the normal course of nature, but the probability is not precisely zero.

This toy model neglects other important physical effects, but it suffices to demonstrate the point that a lot of physical systems are largely governed by probabilities. Personally, I think this is how God has built leeway into the system of the universe to do the seemingly impossible in the natural world without violating the laws of nature. It is God, or an agent of God, doing what is effectively impossible, i.e. impossible for us, but not strictly impossible, and certainly not impossible for God.

Let’s consider a biblical example — the parting of the Red Sea. In Exodus 14, Moses is described as stretching out his hand at God’s command and parting the Red Sea so that the millions of people of Israel could cross it and escape from the pursuing Egyptians. This is referenced later in Deuteronomy 26:8 as one of the “signs and wonders” (oth and mopheth) God used to display his power and free Israel from Egypt. The probability of finding the waters of the Red Sea spontaneously parting on their own would be as exceptionally low as in our example of the air molecules in the room spontaneously arranging themselves on just one side. It’s so low that we would never expect it to happen in the usual course of nature, but, as we saw in the example of air molecules, it’s not strictly impossible.

Do not misunderstand me. I am not: a) claiming that all physical miracles have a foundation in probability — the miracle (semeion) of Jesus turning water into wine would involve a different physical mechanism than that illustrated by statistical thermodynamics; b) claiming that all miracles are physical in character; or c) attempting to explain miracles in a way that detracts from their miraculousness. That physical miracles could fit into the natural framework of the universe makes them no less wondrous than if they defied the laws of nature. Think of it this way. It’s not strictly impossible for you to win the Mega Millions lottery four times in a row — the probability is approximately 1 out of 1025, about 100,000 times more probable than finding 100 air molecules on one side of a room. However, the odds are so overwhelmingly against it that it no one would believe it happened without someone intervening in the system to force this outcome. Isn’t that what we’re talking about with miracles?

According to the laws of physics, a miracle like parting the Red Sea does not violate the laws of nature, it just requires a far greater power over the forces of nature than we humans could ever have.

In the next part, I’ll look at miracles from the perspective of the weird and wondrous world of quantum mechanics.

Since posting, I’ve lightly edited this article for clarification of two points: 1) not all physical miracles are probabilistic in nature; and 2) not all miracles are physical in character. Some miracles described in the Bible, such as the creation of the universe, the creation of the nefesh (animal soul) and the neshama (human soul), and Jesus’ resurrection and ascension, are entirely supernatural in character.

Parting of the Red Sea image credit: The Swordbearer.