Traffic’s up after the announcement of the publication of our Astronomy and Astrophysics curriculum, so we’re replaying some of our more important posts from the archives for our new readers. This article was originally posted on February 21, 2012.

So says Tufts University physicist, Alexander Vilenkin, who made this statement at a meeting in January in honor of Stephen Hawking’s 70th birthday. (I’m a little late getting around to this, but it’s worth commenting on.)

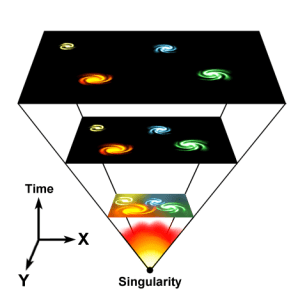

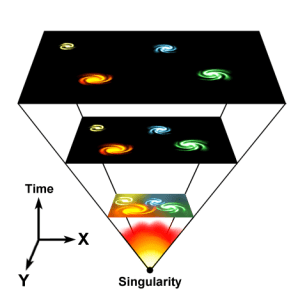

To fully appreciate the magnitude of this statement, consider that the prevailing view of cosmology for more than two thousand years was that of an eternal universe. This view began to change in the 1920s, when astronomer Edwin Hubble discovered that the spectra of most galaxies are redshifted, and the further away a galaxy is from the Milky Way, the more its spectrum is redshifted. What this means in plain English is that almost all of the galaxies he observed are rushing away from each other, and those that were further away are rushing away faster. Incredibly, it appeared the universe was not only changing, but expanding. If you imagine running the expansion in reverse, so that galaxies rush toward one another as you go back in time, you end up with a point at which the expansion started — a beginning in time and space.

Belgian physicist and priest, Georges Lemaître, anticipated this discovery with what he called the “hypothesis of the primeval atom,” based on his solution to the Einstein field equations. The universe’s beginning was predicted to have been very energetic and violent, and was therefore dubbed as the “big bang.” Four decades later, physicists Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson discovered the predicted afterglow of this big bang, which eventually earned them Nobel prizes. By the late 1980s, sophisticated satellites were mapping the tiny fluctuations in the intensity of the big bang afterglow, which allowed physicists to calculate an age for the universe. By the end of the 20th century, there was near-consensus that the universe had a beginning that occurred some 11-17 billion years ago. (The cosmological model-based number is ~14 billion years.)

The big bang has had its detractors. It was astrophysicist Fred Hoyle, out of deep skepticism for the idea, who sarcastically applied the term “big bang” to this cosmological model. (Let it not be said that physicists are overly sensitive — the term stuck and has been used in all seriousness ever since.) Hoyle’s collaborator, astrophysicist Geoffrey Burbidge, famously ridiculed physicists who had hopped on the big bang bandwagon as “rushing off to join the First Church of Christ of the Big Bang.” There were two reasons scientists reacted this way. First, some scientists found the idea of a universe with a beginning uncomfortably close to the Genesis account of creation. Second, from the point of view of physics, mathematics, and philosophy, a universe with a beginning is far more messy to deal with than an eternal universe, which requires no explanation. Even still, the evidence for a beginning is now so overwhelming that most physicists have come to accept it, and the big bang has become the prevailing paradigm governing all of physics.

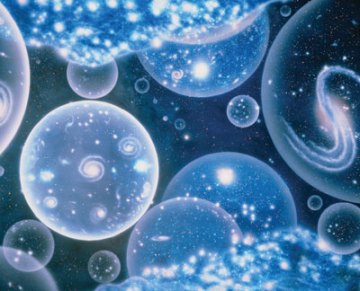

Nevertheless, some physicists had not given up on the idea of an eternal universe, but the focus changed to devising sophisticated models for an eternal universe that fit the observed data — in other words, an eternal universe that incorporated key features of the big bang model. Some of these features are explainable by invoking what’s called inflation, which refers to an early period of exceedingly rapid expansion. This idea was proposed by Alan Guth in the 1980s, and it can also be applied to an eternally inflating universe in which regions of the universe undergo localized inflation, creating “pocket universes.” This inflation continues forever, both in the past and into the future, and so in a sense it represents an eternal universe. Another idea was the cyclical universe, which posited that the universe is eternally expanding and contracting. In this way, the big bang that occurred 14 billion years ago would be just one of an infinite number of big bangs followed by ‘big crunches.’

All of the evidence indicates ours is a universe undergoing perpetual change. To replace Aristotle’s age-old idea of an eternal, unchanging universe, physicists came up with hypothetical eternal universes that were perpetually changing. This was an ingenius approach, but as Vilenkin announced last month, they just don’t work. Guth’s idea turns out to predict eternal inflation in the future, but not in the past. The cyclical model of the universe predicts that with each big bang, the universe becomes more and more chaotic. An eternity of big bangs and big crunches would lead to a universe of maximum disorder with no galaxies, stars, or planets — clearly at odds with what we observe.

As the journal New Scientist reports, physicists can’t avoid a creation event. Vilenkin’s admission exemplifies the reason physics is the king of all the sciences — physicists are generally willing to admit when their cherished ideas don’t work, and they eventually go where the data and logic lead them. Whether this particular realization will pave the way to serious discussion of God and consistency with the Genesis account of creation remains to be seen. Physicists can be a stubborn bunch. As Nobel laureate George P. Thomson observed, “Probably every physicist would believe in a creation if the Bible had not unfortunately said something about it many years ago and made it seem old-fashioned.” Still, some physicists are open to the idea. Gerald Schroeder, who is also an applied theologian, has written profoundly on the subject. His book, The Science of God, is an illuminating discussion of how the Bible and biblical commentary relate to the creation of the universe.