In which we discuss inflation, the multiverse, and fine-tuning.

I had the following exchange with a reader in the comments of a previous post:

jlafan2001: What is your take on the discovery of cosmic inflation? Isn’t inflation evidence of a multiverse and doesn’t that refute the fine-tuning argument?

SS: Inflation is a compelling idea that answers some big cosmological questions, and, personally I think it’s correct. One flavor of multiverse — the bubble universe idea — is an outgrowth of the inflationary big bang model. The problem for a multiverse based on inflation is that inflation is also consistent with non-multiverse models. There is currently no way to distinguish between them based on the evidence. There is, to my knowledge, nothing that can be confidently stated about the multiverse based on evidence, therefore it would be beyond foolishness to say that the multiverse constitutes a genuine refutation of the fine-tuning argument.

jlafan2001: Thank you for your input, Dr. Salviander. Why would scientists then use the inflation model as evidence for the multiverse if it can go either way?

A not unreasonable question. The answer is, inflation is one of the very few (ambiguous) lines of evidence atheist scientists have for the multiverse, and there is considerable philosophical motivation to support the multiverse no matter how weak the evidence.

There are two main problems in physics for the atheist scientist:

- The big bang. A universe with a beginning logically implies a supernatural creative force for the universe.

- The fine-tuning of the universe, for which there are only three explanations: a) necessity; b) chance; c) design.

Contrary to what Young Earth Creationists believe, atheist scientists have never been happy with the big bang. To understand why, all you have to do is go back to February of 1961 when striking evidence in favor of the big bang was presented at a meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society in London. That evidence would later turn out to be flawed, but at the time it inspired some notable headlines in London newspapers. The Evening Standard published an article with the headline “‘How it all began’ fits in with Bible story” (Peter Fairley, 10 February 1961), and the Evening News and Star featured an article headlined, “The Bible was right” (Evening News Science Reporter, 10 February 1961).

These headlines reflected the big bang’s astounding confirmation of the first three words of the Bible. To understand the significance, consider that for millennia prior to this, the scientific consensus was that the universe was eternal. Obviously, this was a big problem for the Bible-believers, but not for atheists, who rested assured that the universe required no explanation. That all started to change in the 1920s with solutions to Einstein’s general relativity equations showing the universe could be dynamic, as well as Hubble’s evidence that the universe is expanding. Things finally changed in a big way in the 1960s with the discovery of the cosmic microwave background, which pretty much sealed the deal for the big bang.

To their credit, the vast majority of physicists accepted the big bang theory once there was sufficient evidence, even if a lot of them didn’t like it. However, there were a few notable holdouts, like renowned astrophysicist and atheist, Geoffrey Burbidge. It’s not a stretch to suggest that his steadfast support for an eternal universe in spite of the evidence was philosophically motivated, especially considering he famously accused many of his colleagues of “rushing off to join the First Church of Christ of the Big Bang.”

The evidence for the big bang is by now so overwhelming that few physicists doubt it. That leaves atheist physicists with a big problem, which is how to offer an alternative to God as the supernatural creative force behind the universe. Thus, we have the multiverse.

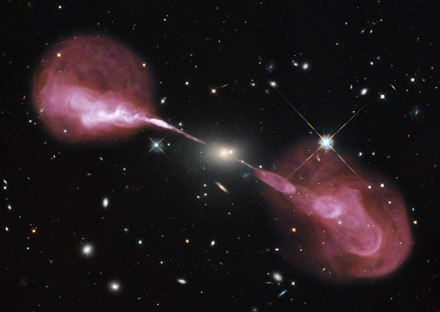

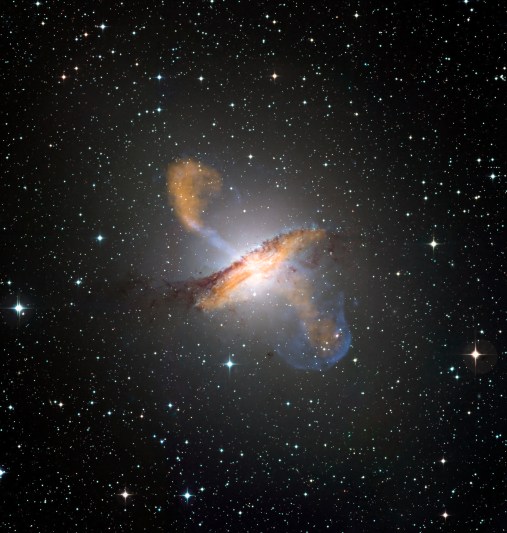

Now, it’s important to point out that, contra what some skeptical Christians believe, physicists did not metaphorically pull the multiverse out of a magician’s hat. There are different types of multiverse (or “levels” as physicist Max Tegmark calls them), each with a basis in physics and mathematics that makes the idea conceptually somewhat compelling. One level of multiverse is the bubble universe model. This model says that inflation — a period of extremely rapid expansion of the universe shortly after the big bang — leads to regions of localized inflation, which form like bubbles in a cosmic sea of foam. Each of these bubbles expands at such a rate that they are all causally cut off from each other, and each effectively forms its own universe. This is one type of inflationary universe; there are others that do not lead to multiverses. However, as I pointed out to jlafan2001, there is no way I’m aware of that you can observationally distinguish between an inflationary bubble universe and an inflationary non-bubble universe.

So, how does this tie into fine-tuning?

The fine-tuning argument says this: the many observable parameters of the universe that permit human life to exist are so finely-tuned as to strongly imply the universe was designed by a personal being. Physicists have ruled out necessity as an explanation for fine-tuning; this means there is nothing in any physical theory or any extension of physical theory that requires the various physical parameters describing our universe to be the way they are. That leaves chance and design. For an atheist physicist, design is obviously out, which leaves chance as the only explanation. It turns out physicists aren’t very happy about this — they would have preferred necessity as the explanation — but, they’re philosophically stuck with chance. Since there is already a theoretical basis in physics for the multiverse, and chance is built into its framework, atheist physicists latch onto it as a means to explain away the appearance of fine-tuning. It also has the virtue of addressing point #1 above by providing an alternative to God as the creative force behind the universe.

The so-far insurmountable problem with the multiverse is that there is no way to test it. One of the features of the multiverse is that each of the universes within it is causally separated from all of the other universes, which means there is no way we an observe any of them, directly or indirectly. There’s just no way we can peek outside of our universe to see if there are any others. So, we’re left with ambiguous evidence like inflation and “shadow particles” (ugh). Until physicists find a way to get around this problem, which is unlikely, the multiverse remains nothing more than a science-flavored idea.