I’ve had several requests for my testimony in Spanish, so here it is. [The English version is here.] This translation was kindly provided by Nélida Rubio-Diffey.

A lo largo de estos años he recibido numerosas solicitudes para que escriba mi testimonio personal y publicarlo. Me pidieron que diera mi testimonio en una Iglesia Local de Austin como parte de su celebración Pascual, lo que finalmente me obligó a escribirlo aquí. Lo siguiente es una versión adaptada de lo que expuse ese día en la Iglesia.

Nací en los Estados Unidos de América, pero crecí en Canadá. Mis padres eran socialistas y activistas políticos que pensaban que la Columbia Británica en Canadá, sería un mejor lugar para vivir para nosotros, dado que en ese tiempo, ésta tenía el único gobierno socialista de Norteamérica. Mis padres también eran ateos, aunque evitaban ponerse esa etiqueta y preferían la de “agnósticos”. Ellos eran amables, amorosos, y con valores morales, pero la religión no era parte de mi vida. En vez de ello, mi infancia giraba en torno a la educación, particularmente la ciencia. Recuerdo que importante era para mis padres que mi hermano y yo tuviéramos un buen desempeño escolar.

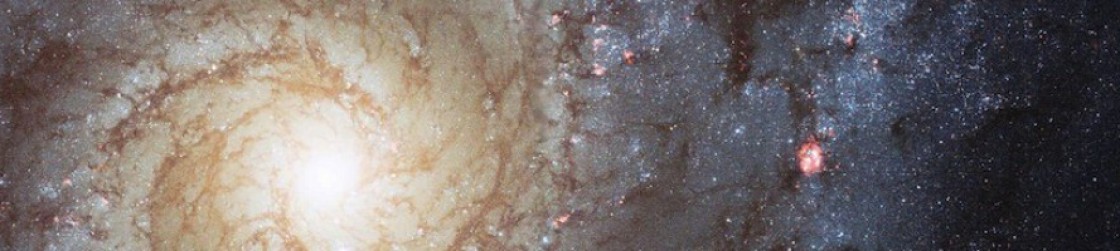

Crecí en las décadas de los setenta y los ochenta, un tiempo en el que la ciencia ficción disfrutaba de un renacimiento, gracias a la extensa popularidad de la serie Star Wars. Recuerdo lo fascinada que estaba con la trilogía original de Star Wars. La cual no tiene casi nada que ver con la ciencia – seria más propiamente caracterizada como una novela espacial – pero me llevo a pensar sobre el espacio en gran manera. También me encantaba la serie original de Star Trek, la cual es más de ciencia ficción. El carácter estoico y razonable de Mr. Spock me era particularmente atractivo. En ese tiempo, la ciencia popular también estaba experimentando un renacimiento, lo cual tuvo mucho que ver con la serie de televisión de Carl Sagan, Cosmos, la cual me encantaba. La combinación de estas experiencias me llevo a tener una curiosidad apasionante sobre el espacio exterior y el universo, en ese tiempo a mis nueve años de edad, ya sabía que algún día sería una científica del espacio.

Para los años setenta, Canadá ya vivía en la era post-cristiana, por lo que yo crecí sin religión. En retrospectiva, es increíble que los primeros veinticinco años de mi vida solo conocí a tres personas que se identificaban como cristianos. A temprana edad mi visión sobre el Cristianismo era negativa y cuando llegue a los veinte años ya era una enemiga activa del Cristianismo. Cuando miro atrás me doy cuenta que mucho de ello era la absorción inconsciente de la hostilidad general en contra del Cristianismo que es común en lugares como Canadá y Europa; Mi hostilidad ciertamente no estaba basada realmente en mi conocimientos sobre el Cristianismo. Yo había llegado a creer que el Cristianismo convertía a la gente en débil e ingenua; pensaba que era filosóficamente trivial. Yo era ignorante no solo de la Biblia, sino también de la profunda filosofía del Cristianismo y de los descubrimientos científicos que clarificaban los orígenes del universo y la vida en la Tierra.

De joven, en mi lucha por comprender el mundo sin la ayuda de la religión, me involucre en el Objetivismo. El Objetivismo es una filosofía fundada en la idea del egoísmo racional. Está basado en el trabajo de la ferviente atea filosofa Ayn Rand, quien vivió en la Rusia Soviética antes de emigrar a los Estados Unidos. A diferencia de mis padres, al principio de mis veintes, yo me acogí al capitalismo en vez de al socialismo. El Objetivismo me atrajo porque defiende la creencia de que mi vida me pertenecía, y de que podía hacer lo que yo quisiera. Parecía una filosofía fuertemente lógica.

A mediados de mis veintes, me mudé a los Estados Unidos para ir a la universidad y prepararme para una vida dedicada a la ciencia. Me inscribí en el programa de física de la Universidad Eastern Oregón, ubicada en el mismo pueblo pequeño donde mi hermano y yo habíamos nacido. Cuando comencé a experimentar la vida como un adulto independiente, empecé a encontrar al Objetivismo como una filosofía árida y estéril.

Ésta había fallado en responder las grandes preguntas: ¿Cual es el propósito de la vida?, ¿De dónde venimos?, ¿Por qué estamos aquí?, ¿Qué pasa cuando morimos?

También padecía de una falta irónica de consistencia interna. A pesar de su enfoque en la verdad objetiva, la filosofía del Objetivismo no tenía ninguna fuente para esa verdad, excepto la opinión humana. Y, a pesar de su enfoque en disfrutar de la vida, los objetivistas no parecían experimentar alegría alguna en absoluto. En cambio, parecían preocupados, con enojo, protegiendo su independencia de todas las presiones externas.

Yo había estado indirectamente apoyando al Instituto de Ayn Rand con una suscripción a una revista objetivista, pero para ese tiempo estaba empezando a arrepentirme. A pesar de que todavía pensaba que el cristianismo era una tontería, los ataques implacables del Instituto de Ary Rand hacia los cristianos estaban empezando a ser tediosos. Y cuando una de las más prominentes figuras públicas del Instituto montó una defensa pública a favor del aborto por parto parcial como un hecho “pro-vida”, cancelé mi apoyo y ya no me identifiqué con la filosofía. Me di cuenta que había dejado atrás al Objetivismo.

Empecé a concentrar toda mi energía en mis estudios, y me dediqué mucho más a mis cursos de matemáticas y física. Me uní a clubes universitarios, comencé a hacer amigos y, por primera vez en mi vida, estaba conociendo cristianos. No eran como los objetivistas – los cristianos eran gozosos y alegres. Y eran inteligentes también. Me quedé asombrada al descubrir que mis profesores de física, a quienes yo admiraba, eran cristianos. Su ejemplo personal comenzó a tener una influencia en mí y me encontré cada vez más menos hostil hacia el cristianismo.

En el verano después de mi segundo año en la universidad, participé en una pasantía de investigación física en la Universidad de California, San Diego. Por primera vez en mi vida, ya no estaba en el centro de masa de la ciencia -el reino de las verdades científicas ampliamente aceptadas- pero me había trasladado a la frontera de la ciencia, donde se estaban haciendo nuevos descubrimientos.

Me había unido a un grupo del Centro de Astrofísica y Ciencias del Espacio (CASS) que estaba investigando evidencia sobre el “Big Bang”. La radiación del origen cósmico- los restos de la radiación de la gran explosión- proporciona la evidencia más fuerte de la teoría, pero los cosmólogos necesitan otras líneas independientes de evidencia para confirmarlo. Mi grupo estaba estudiando la abundancia de deuterio en el universo primitivo. El deuterio es un isótopo de hidrógeno, y su abundancia en el universo primitivo es sensible a la cantidad de masa ordinaria contenida en el universo entero. Lo crean o no, esta medición nos dice si el modelo del Big Bang es correcto.

Si alguien está interesado en cómo funciona esto, lo describiría, pero por ahora les evitaré los truculentos detalles. Basta decir que una sorprendente convergencia de las propiedades físicas es necesaria con el fin de estudiar la abundancia de deuterio en el universo primitivo, y sin embargo, esta convergencia es exactamente lo que conseguimos. Recuerdo haberme quedado pasmada por esto, impresionada, completa y absolutamente asombrada. Parecía increíble para mí que había una manera de encontrar la respuesta a la pregunta que teníamos sobre el universo. De hecho, parece que todas las preguntas que tenemos sobre el universo tienen respuesta. No hay razón para que sea de esa manera, y me hizo pensar en la observación de Einstein, de que la cosa más incomprensible del mundo es que es comprensible. Comencé a sentir un orden subyacente del universo. Sin saberlo, estaba despertando a lo que el Salmo 19 nos dice claramente: “Los cielos cuentan la gloria de Dios; y el firmamento anuncia la obra de sus manos”.

Ese verano, recogí una copia de El Conde de Montecristo de Alejandro Dumas y lo leía en mis horas libres. Anterior a esto, solamente conocía esta obra como una emocionante historia de venganza, ya que eso es lo que las innumerables adaptaciones de cine y televisión siempre habían destacado. Pero es algo más que una historia de venganza, es un examen filosóficamente profundo del perdón y el papel de Dios en impartir justicia. Esto me sorprendió, y estaba empezando a darme cuenta de que el concepto de Dios y religión no eran tan filosóficamente triviales como yo había pensado.

Todo esto culminó un día, mientras caminaba por ese hermoso campus de La Jolla. Me detuve en seco cuando me ocurrió – ¡Yo creía en Dios!, estaba tan feliz; era como un peso que se había quitado de mi corazón. Me di cuenta de que la mayor parte del dolor que había experimentado en la vida era de mi propia creación, pero que Dios lo había usado para hacerme más sabia y compasiva. Fue un gran alivio el descubrir que había una razón para el sufrimiento, y era porque Dios era amoroso y justo. Dios no podía ser perfectamente justo a menos que yo- justo como cualquier otro – estaba hecha para sufrir por las cosas malas que había hecho.

Durante un tiempo estuve contenta de ser una teísta y no perseguí a la religión más allá. Pasé un verano muy agradable en el CASS, y luego durante mi último año en la Universidad conocí a un hombre que me gustó mucho, un estudiante de ciencias de la computación proveniente de Finlandia. Él había estado en las fuerzas especiales de la Fuerza de Defensa de Finlandia, y tenía un carácter de lo más bizarro que he conocido. Pero también era un hombre de fuerza, honor e integridad profunda, y me encontré poderosamente atraída por esas cualidades. Al igual que yo, él había crecido siendo ateo en un país laico, pero había llegado a aceptar a Dios y a Jesucristo como su salvador personal cuando tenía unos veinte años, a través de una experiencia personal intensa. Nos enamoramos y nos casamos. De alguna manera, a pesar de que yo no era religiosa, me sentí reconfortada al casarme con un hombre cristiano.

Ese año me gradué de la licenciatura en física y matemáticas, y en el otoño, comencé estudios de posgrado en astrofísica en la Universidad de Texas en Austin. Mi esposo estaba un año detrás de mí en sus estudios, por lo que me trasladé sola a Austin. El programa de astrofísica en la Universidad de Texas era en un ambiente mucho más riguroso y desafiante que en mi pequeña alma mater. El rigor académico, combinado con el aislamiento que sentí de mi familia y amigos que estaban lejos, me dejó bastante desanimada.

Un día paseando por una librería, vi un libro llamado La ciencia de Dios por Gerald Schroeder. Estaba intrigada por el título, pero algo más me obligó a leerlo. Tal vez fue la soledad, y yo estaba deseando una conexión más profunda con Dios. Todo lo que sé es que lo que leí me cambió la vida para siempre.

El Dr. Schroeder es un individuo único, es un físico entrenado en el MIT y también un teólogo aplicado. Él entiende la ciencia moderna, ha leído los comentarios bíblicos medievales y antiguos, y es capaz de traducir el Antiguo Testamento del hebreo antiguo. Por consiguiente fue capaz de hacer un análisis científico de Génesis 1. Su trabajo me demostró que Génesis 1 era científicamente sólido, y no sólo un “mito tonto” como los ateos creían. Me di cuenta de que, sorprendentemente, la Biblia y la ciencia están de acuerdo por completo. (Si usted está interesado en los detalles de esto, bien puede conocerlos a través de mi presentación o leer el libro del Dr. Schroeder.)

El gran trabajo de Schroeder me convenció de que Génesis es la palabra inspirada por Dios. Pero algo me llevó más allá. Si Génesis es literalmente cierto, entonces ¿por qué no los Evangelios, también? Leí los Evangelios, y encontré a la persona de Jesucristo extremadamente cautivadora. Me sentí como Einstein cuando dijo que estaba “fascinado por la figura luminosa del Nazareno.” Y sin embargo aún luchaba, porque no me sentía cien por ciento convencida de los Evangelios en mi corazón. Yo sabía de la evidencia histórica de su verdad. Y por supuesto, sabía que la Biblia era fiable debido a Génesis. Intelectualmente, sabía que la Biblia es verdad, y como una persona de intelecto tuve que aceptarlo como verdad, aunque no lo sintiera así. Eso es lo que es la fe. Como dijo CS Lewis, es aceptando algo que usted sabe que es verdad, a pesar de sus emociones. Así que, me convertí. Acepté a Jesucristo como mi salvador personal.

Tal vez esto suena fríamente lógico. Me lo parecía a mí, y por esa razón a veces me preocupaba si mi fe era real. Pero entonces, hace un par de años atrás tuve la oportunidad de descubrirlo. Ese año comenzó con mi diagnóstico de cáncer y un tratamiento desagradable. No mucho tiempo después, mí esposo se enfermó de meningitis y encefalitis, y no estaba claro si iba a recuperarse; no sabíamos si estaría paralizado o peor. Le tomó cerca de un mes, pero afortunadamente, se recuperó. En ese momento, estábamos esperando nuestro primer hijo, una niña. Todo parecía bien hasta los seis meses, cuando nuestra bebé dejó de crecer. Nos enteramos de que tenía trisomía 18, una anomalía cromosómica fatal. Nuestra hija, Ellinor, nació muerta poco después.

Fue la pérdida más devastadora de nuestras vidas. Durante un tiempo perdí la esperanza, y no sabía cómo podría continuar después de la muerte de nuestra hija. Pero finalmente tuve una clara visión de nuestra niña en los brazos amorosos de su Padre celestial, y fue entonces cuando tuve paz. Reflexioné que, después de todas esas pruebas vividas en un año, mi esposo y yo, no sólo estábamos más cerca entre sí, pero también más cerca de Dios. Mi fe era real.

No sé como hubiera hecho frente a tales pruebas cuando era atea. Cuando se tienen veinte años, estas saludable, y tienes a tu familia alrededor, te sientes inmortal. Nunca pensé en mi propia muerte o la posible muerte de mis seres queridos. Pero llega un momento en que el sentimiento de la inmortalidad se desvanece, y te encuentras obligado a enfrentar lo inevitable, no sólo tu propia aniquilación, sino la de tus seres queridos.

Hace unos años, cuando estaba investigando un artículo sobre la naturaleza del tiempo, me sorprendí al descubrir que sólo las creencias abrahámicas y sus ramificaciones se sostienen en un tiempo lineal. Todas las demás tradiciones religiosas se sostienen en un tiempo cíclico. No sólo el tiempo cíclico parece más intuitivamente correcto -nuestras vidas se rigen por muchos ciclos en la naturaleza- sino que ofrece una conexión reconfortante con lo Sagrado a través del eterno retorno. La versión moderna y laica de esto es el Multiverso.

Georges Lemaître fue un sacerdote belga y físico que resolvió las ecuaciones de la relatividad general de Einstein y descubrió que, en contra de la filosofía predominante de los últimos 2,500 años, el universo no era necesariamente eterno y estático. Descubrió en su solución la evidencia matemática de un universo en expansión, y lo discutió vigorosamente. Por esa razón, se le considera el padre de la gran explosión – el Big Bang – (a lo que él llama “la hipótesis del átomo primitivo”). Poco antes de morir, se le dijo que su hipótesis había sido reivindicada por el descubrimiento de la radiación del origen cósmico, la predicción más importante de la hipótesis. Este descubrimiento también reivindicó las primeras palabras de la Biblia después de 2,500 años de duda- hubo un principio. Y ese principio significaba que el universo tuvo una causa trascendente, pues nada en la naturaleza es su propia causa. Los ateos se consternaron por ello y se vieron obligados a retractarse de la idea del Multiverso.

La idea del Multiverso postula que hay un enorme número, posiblemente un número infinito, de universos paralelos. Es una idea interesante, pero en última instancia no es científica. La ciencia sólo puede estudiar lo que podemos observar en este Universo. No puede inclusive tener la esperanza de estudiar el Multiverso. Sin embargo, algunos ateos se aferran a la idea, porque es la única alternativa seria a Dios, como la fuerza creativa detrás del Universo y es una manera de hacer frente a la mortalidad en la ausencia de Dios. El problema es que la mayoría de los defensores del Multiverso no han explorado seriamente sus implicaciones lógicas. Creo que, cuando lo hacen, su visión del mundo les lleva a la desesperanza.

Hugh Everett es un ejemplo de ello. Él era un brillante físico que es conocido por lo que se llama “La interpretación de muchos mundos de la mecánica cuántica”. Trató de explicar los efectos extraños, casi místicos, del mundo cuántico al rechazar su dependencia de las probabilidades. Propuso en cambio que todos los posibles resultados de cada experimento realmente suceden, pero suceden en universos alternativos. Esta fue la primera encarnación científica del Multiverso.

Everett no estaba motivado únicamente por las matemáticas. Él entendió las implicaciones de sus creencias ateas, y estaba buscando una manera de escapar de la aniquilación que es inevitable en la cosmovisión atea. Para él, la idea de muchos mundos era una forma de inmortalidad. Quería creer que había un número infinito de Hugh Everetts, todos habitando en estos universos alternos, porque era una manera de evitar el terror de la aniquilación. Pero, como Jesús nos dijo, debemos juzgar a un árbol por sus frutos. La visión del mundo de Everett no le ofreció a él, ni a su familia, confort verdadero alguno. Él era un alcohólico deprimido que se consumió, bebió y fumó hasta la muerte, a la edad de 51 años. Su hija se suicidó años después, e indicó en su nota de suicidio que ella esperaba terminar en el mismo universo paralelo que su padre.

En el Multiverso no somos únicos; hay muchas “copias” de cada uno de nosotros. Si es real, entonces hemos vivido y viviremos un número infinito de vidas. De hecho, ya hemos vivido esta vida exacta un número infinito de veces. Todas esas vidas están perdidas y sin sentido. Viviremos un número infinito de veces de nuevo. Everett y otros que creen en el Multiverso no han vencido a la muerte; creen que han encontrado una forma de engañarla, pero esta forma de “inmortalidad” es en realidad una prisión de la que no hay escapatoria. ¿Eso te suena horrible? Suena horrible para mí. Al igual que con la filosofía de Ayn Rand, el Multiverso es en última instancia estéril de fe y propósito.

No creo que estemos encerrados en esa especie de prisión. Pero la única forma de ser libre es si el universo y todo lo que hay en él fueron creados, no por algún mecanismo inconsciente, pero por un ser personal -el Dios de la Biblia-. La única forma en que nuestras vidas son únicas, con propósito, y eternas es si un Dios de amor nos creó.

****

Amo mi carrera de astrofísica. No puedo pensar en nada que prefiera hacer que estudiar el funcionamiento del universo, y me doy cuenta ahora que mi fascinación de toda la vida con el espacio ha sido realmente un intenso anhelo de una conexión con Dios (“Porque desde la creación del mundo las cualidades invisibles de Dios – su eterno poder y deidad – se hacen claramente visibles, siendo entendidas por medio de las cosas hechas “[Romanos 1:20]). Pero también siento un fuerte llamado a ministrar a otros a través de este mismo trabajo.

Nunca olvidaré a la estudiante que me inició en este camino. Cuando yo era estudiante de posgrado, no mucho después de que me había convertido al cristianismo, estaba auxiliando dirigiendo una sesión de un curso de astronomía, y estábamos hablando sobre la cosmología del Big Bang. Después de la sesión, la estudiante vino a mí y muy tímidamente me preguntó, si estaba bien ser un científico y creer en Dios. Le dije, por supuesto; Yo era científica y creía en Dios. Ella estaba visiblemente aliviada, y me dijo que uno de sus profesores en otro departamento había dicho que no se podía ser religioso y creer en la ciencia a la misma vez. Estaba angustiada por esto, y me pregunté cuántos otros jóvenes estaban luchando con preguntas similares acerca de la ciencia y la fe. Me decidí a ayudar a otros que están luchando con dudas. También quería ayudar a la gente a responder con seguridad a los argumentos ateos falsos. He luchado con esto, porque sé que va a ser un camino difícil de recorrer. Pero el significado del sacrificio de Jesús no me deja ninguna duda acerca de lo que tengo que hacer.

Cuando estaba en el proceso de convertirme en creyente, dos cosas me atrajeron a Dios, la abrumadora evidencia de su implicación en el mundo físico y su justicia perfecta. Yo puedo ayudar a la gente a ver la obra de Dios en el mundo físico, pero no estoy cualificada con justicia perfecta. Ninguno de nosotros está. La justicia perfecta de Dios exige la expiación del pecado, pero debido a nuestra naturaleza imperfecta, no somos capaces de llevar a cabo la expiación. Dios envió a su Hijo unigénito, Jesucristo, para la expiación por nosotros. Jesús fue crucificado, murió y fue sepultado, y al tercer día resucitó. Se logró la justicia perfecta.

Jesús triunfó sobre la tentación, el pecado y la muerte. Si optamos por aceptar el regalo de la salvación, somos reconciliados con Dios: “ Porque de tal manera amó Dios al mundo, que ha dado a su Hijo unigénito, para que todo aquel que en él cree, no se pierda, mas tenga vida eterna.” (Juan 3:16 ) No sé quién es usted, querido lector, o cual sea su pasado. Tal vez usted es un creyente; si es así, usted ya conoce el poder de estas palabras. Pero si usted todavía está buscando a Dios, quizás usted elegirá, como lo hice yo, aceptar este gran regalo de la salvación y reconciliarse con Dios.