Traffic’s up after the informal announcement of the publication of our Astronomy and Astrophysics curriculum, so in the coming weeks we’re going to replay some of our more important posts from the archives for our new readers.

On March 30, 2011, Christian theologian and philosopher William Lane Craig debated atheist physicist Lawrence Krauss at North Carolina State University. The topic was, “The Great Debate: Is There Evidence for God?” Video of the rather lengthy event is here. What follows is our analysis of the debate.

** Written by Sarah and “Surak” **

The two opposing sides of the scientific debate over the God hypothesis were well represented on Wednesday by Dr. William Lane Craig (Christian Philosopher and Theologian from Talbot School of Theology) and Dr. Lawrence Krauss (Theoretical Physicist from Arizona State University). Dr. Craig’s argument was based on the clearly-stated and logical assertion that if God’s existence is more probable given certain information, that information meets the essential criterion for evidence. Dr. Krauss was equally clear in his definition of evidence: it must be falsifiable to be scientific. We find both standards to be very useful.

There was some confusion on the part of the moderator as to whether the topic of the debate was the existence of any evidence for God or the existence of enough evidence to prove God’s existence. We think the moderator erred in his statement of the debate’s purpose, since no one could reasonably argue that there is proof or disproof of God’s existence. As Dr. Krauss correctly stated, science cannot falsify God; so, the question can only be, “Is God likely?”

We will assess the debate in terms of whether or not there is any evidence for the existence of God, although Dr. Krauss tried to set the bar unfairly high with his assertion that a highly extraordinary proposition, such as the God hypothesis, requires extraordinary evidence. However, we think defenders of the God hypothesis can accept and meet this challenge.

Dr. Krauss acknowledges that the big bang is fact and one of science’s great achievements. The big bang theory establishes that the universe had a beginning, and that the universe was created from nothing. There was some debate and confusion about the meaning of “nothing.” It can mean the absence of matter, such as in “empty” space, or it can mean no space, no matter, and no time. The big bang involves the second notion of nothing, which is about as much of a nothing as most human minds can conceive of.

The appearance of our universe from this nothing makes it an undeniable instance of creation – something coming from nothing – as opposed to an example of making, which is something being fashioned from something that’s already there. Science is based on the premise that everything has a cause, especially if it has a beginning. Since the universe had a beginning, it must have a cause, and a reasonable extension of the big bang theory is that the cause must be something greater than and outside of the universe.

The cause of our universe must therefore be a transcendent or super-natural cause. This ultimate cause must include not only the difficult idea that some entity “exists” outside our universe, but also the humanly inconceivable idea that it has as part of its nature the capacity to exist and make other things come into existence. In other words, there must be something that is its own cause and the essence of existence. We humans can never understand such an entity, but it’s the only way to avoid a common patch of logical quicksand that threatens to swallow anyone who attempts to discuss the origins of our universe.

This danger to fruitful discussion is best illustrated by a story that appeared in Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time. One of the greats of science, probably Bertrand Russell, had given a lecture on astronomy. He described how the Earth orbits around the Sun and how our solar system is part of a much larger galaxy. After the lecture, he was approached by a little old lady who informed him that the Earth is really sitting on the back of a giant tortoise. Russell replied, “What is the tortoise standing on?” “You’re very clever, young man, very clever,” said the old lady. “But everyone knows it’s turtles all the way down!” We must accept that at the bottom of any conceivable pile of cosmic turtles, there must ultimately be one that has as part of its nature the power of existence.

There is perhaps only one relevant or useful question humans can pose about this scientifically unknowable causal agent of the universe, “Is it conscious or unconscious?” If the transcendent cause of the universe is conscious, God is the most useful name we can give it. If the cause of the universe is unconscious, then it is some kind of super-nature. The best known and most likely candidate for the super-natural is the ‘eternal multiverse.’

This brings us to what we thought was the best question from the audience: What testable prediction does the God hypothesis make? Let’s examine this question in light of two things that Dr. Krauss said:

- Truly scientific evidence must be falsifiable.

- The big bang is established fact.

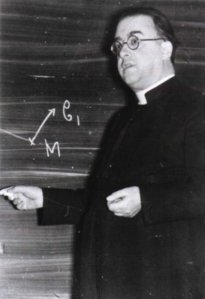

The Judeo-Christian God hypothesis includes a prediction made over 3,000 years ago in Genesis 1 that the universe had a beginning. This prediction ran counter to the theory of an eternal universe that dominated philosophical and scientific thinking until the 1960s. The great physicist and Jesuit priest, Georges Lemaître, developed the big bang theory in part because of his belief in the Genesis account of Creation. This Genesis prediction was testable and turned out to be true. So, at least one major testable prediction of the God hypothesis meets the standard for scientific evidence.

It is not proof of God, but it is undeniable evidence for God that meets even the “extraordinary” benchmark set by Dr. Krauss. The prediction that the universe had a beginning is more than ordinary evidence because it is so ancient. It turns Dr. Krauss’s somewhat derisive comment about Bronze Age peasants back on his own argument: how indeed could such scientifically ignorant people have boldly stated what would three millennia later become astonishing fact?

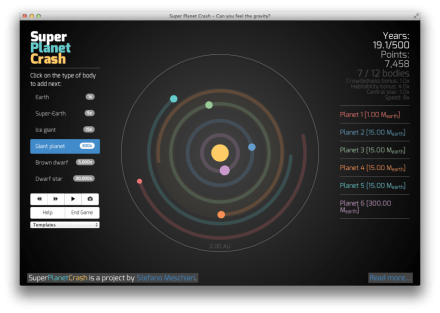

Apply the same test to the best super-nature alternative: what testable prediction(s) does the multiverse hypothesis make? We are still learning about the different multiverse hypotheses, but there are at least two predictions that we’re aware of. The first involves an explanation for the weakness of gravity, which is by far the weakest of the four fundamental forces of nature. Some physicists predict that gravity is weak, because gravitons – the particles responsible for conveying the force of gravity – escape our universe into parallel universes.

The second prediction is the existence of “ghost particles” from parallel universes. Some physicists believe these particles must exist in order explain one of the great mysteries of quantum physics, the interference pattern observed when electrons pass through a double-slit. Interference is behavior we expect from waves, not particles; moreover, the pattern is observed even if electrons are fired at the double-slit one at a time, ruling out any possibility that two electrons, each going through a different slit, are interfering with each other. The interference pattern must arise, the prediction goes, from the electrons in our universe interfering with ghost electrons in a parallel universe.

There are two insurmountable problems with these predictions. Not only do they contradict Dr. Krauss’ assertion that parallel universes are causally disconnected from each other, but neither of these predictions is testable. The evidence for the multiverse does not rise to the level of the scientific — not because we currently lack the knowledge or technology to perform the experiments, but because they are not falsifiable in principle. Science is limited to the study of this universe. The multiverse idea as it is currently framed is not scientific, it is metaphysical.

It seems that at this time the God hypothesis is superior in evidence to the best “natural” alternative.

The evidence in favor of the God hypothesis is even stronger than what Dr. Craig presented. We at SixDay Science propose that the Genesis 1 account of Creation makes at least 26 scientifically testable statements. All 26 are compatible with modern science and they are in the correct order. A discussion of this is available here. We believe this evidence is so extraordinary that it comes close to being something akin to J. B. S. Haldane’s “Precambrian rabbit” in the sense that a creation story which succeeded in anticipating so much of modern science by 3,000 years is just as out of place in time as a fossilized rabbit in 600 million year old rock.