The following is a comment left by a reader at Vox Popoli about a year ago, in response to another reader who was concerned about the current state of science. I had written the following response with the intention of posting it here, and then forgot about it. Surak is about to offer some commentary on a disturbing development in science that bears on this, so I figured now was a good time to dig it up and post it.

To answer your question as to what ever happened to the scientific method, here’s the shocking truth: Science does not operate according to the scientific method unless there’s a crisis. Never did.

Science, just like every other avenue of human endeavor (why should it be different, honestly?) operates under the thrall of a power structure. Always has.

The scientific method only applies when challenges come up against prevailing paradigms. Then, it is utilized, and don’t be a fool understand that every effort is made, always, to doom the challenger and to favor the prevailing paradigm.

The great merit of the scientific method is that under these rare conditions reason and proof hold sway. But please do not be so foolish as to assume that science is governed by the scientific method on a basis, because it is not.

Science is governed by egos. And nothing more.

It is true in a grand Kuhnian sense that crisis precedes advancement. It is also true that egos are a factor in science. But so what? Science is the triumph of the human mind over ego and a multitude of other human failings—limited perspective, misleading emotions, dominant philosophies that act as closed boxes, and the corrupting effects of the universal desire for fame, fortune, and/or political power. The scientific method is the means by which these frailties are remedied. Since these obstacles to advancements in knowledge will always be with us, there will always be a turbulent interplay between human nature and the pursuit of science.

The key element of the scientific method that keeps it from flying off in the direction of wild, unsubstantiated speculation is the peer-review process. If you want to know if the scientific method is alive and well in any branch of science, simply observe how rigorously the peer-review process is being used. I go through the peer-review process on several levels every time I submit a research paper for publication.

The first hoop I have to jump through is the judgment of the referee assigned by the journal in which I hope to have my paper published. The most important thing the referee does is check how well I have accomplished the observe –> hypothesize –> predict –> test –> theorize part of the process. If the judgment is that my work is scientifically sound, the paper is published. Then the whole body of my profession passes judgment on my work by deciding whether or not to cite my work. At the next level of the peer-review process, decisions are made about which scientists are deserving of funding, tenure, and promotions. At the final level, judgments are made about which work is deserving of awards. The end result of this in physics is a steady advance in knowledge where occasional detours from truth are corrected and dead ends are usually recognized and reversed.

I accept that there are some areas of science in which the scientific method does not currently function as it should. So-called “climate change science” is the most obvious example of science being corrupted by politics, money, and dogma. Surak will have something to say about this soon with regard to a disturbing development in this field. Meanwhile, there is a simple test one can apply in this regard: any time the name Al Gore or the terms “scientific consensus” and “the debate has been settled” are used in regard to any branch of science, it has undoubtedly strayed from the scientific method.

Biology certainly suffers from an ego problem to the extent that it is nearly impossible to get a mainstream biologist to utter the words, “Darwin was wrong about some important things.” He was wrong about some important things, and a paradigm shift is long overdue in the field of evolution. But, it must be acknowledged that a multitude of biologists are doing very good work that is firmly based on the scientific method.

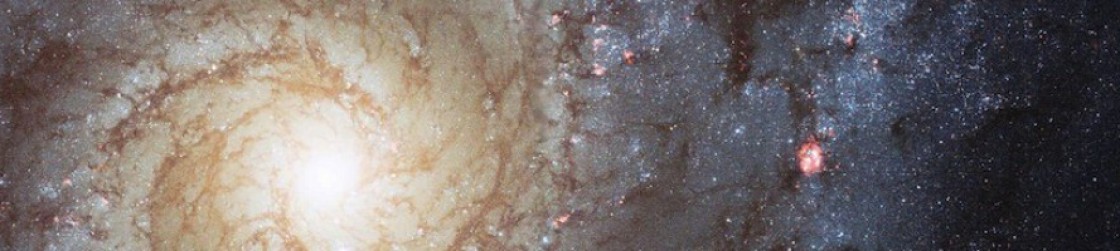

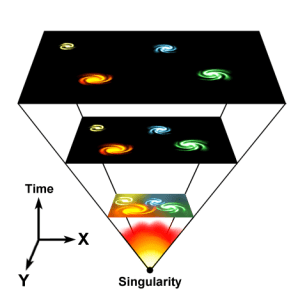

The real test of any field’s application of the method is whether that field petrifies into dogma or if it routinely accepts change. I must speak in defense of my field of physics/astrophysics. It has a long history that includes the initial establishment of the scientific method as well as continuous successful applications of its process. After the Copernican revolution and the invention of precision clocks, experimental methods were sufficiently advanced that it didn’t take all that long to accumulate enough evidence to overthrow old ideas and adopt new paradigms. To name but a very few examples: Newton’s uniting the heavens and the earth under one set of laws, Maxwell’s unification of electricity and magnetism, Poincaré’s relativity of time and space, Planck’s quantum, Hubble’s confirmation of other galaxies and the expanding universe, Einstein’s new view of gravity, Lemaître’s big bang theory, Zwicky’s dark matter, and the supernova teams’ accelerating universe.

You say this is rare, but how often do you think this is supposed to happen? How often can it happen on such a large scale? The Hubble/Lemaître paradigm is an especially important example of the scientific method working as well as it possibly can. Most physicists did not like the idea of a universe with a beginning, but the scientific method is so firmly established in physics that the vast majority of them accepted it once there was sufficient evidence to overcome all reasonable objections. Those who clung to the notion of the eternal universe for reasons of ego and non-scientific concerns were discredited for straying from the scientific path.

The application of the scientific method does not have to be perfect to be functional. My own everyday experience in the field of astrophysics has been that the method sometimes proceeds as the classic observe -> hypothesize -> predict -> test -> theory. But quite often it is something very different: observe -> huh? -> observe -> what the … ?! -> hypothesize -> predict -> test -> getting close to a theory! -> test again -> wait, what? -> OH! -> hypothesize -> test, and so on. As long as it is evidence- and prediction-driven throughout the confusion, that’s good enough.

As for the system being set up to doom the challenger, how else would you have it? That’s the way it should be, as long as this resistance is not rooted in ideology (e.g. “climate change science”). It’s not unlike a court of law, where the presumption should be the innocence of the accused and the burden of proof lies with the accuser.

Egos, admittedly, often get in the way of true science, but on the other hand I doubt science could proceed without them. Scientists will always be fully human and infinitely closer in nature to Captain Kirk than to Mr. Spock. The vast majority of people I work with are truly driven by a desire for truth, but also the competitive hope for recognition and reward (which is why science has always been a traditionally masculine endeavor). And yes, they also have an understandable instinct to protect the fruits of their labor.

The point of all this, do not confuse the inevitable imperfect application of the scientific method for its absence.