People in the modern West take for granted that events proceed in a line stretching from the past through the present and into the future. They also believe that each point in time is unique—two events can be very similar, but no event or chain of events is ever exactly repeated. This view of time is called linear time, and it is so deeply ingrained in Westerners from birth that it is difficult for them to imagine any other view of time. However, the overwhelming majority of people who have ever lived have had a very different view of this fundamental aspect of existence.

Non-linear time

The alternative to linear time is a belief that time endlessly repeats cycles. I have great difficulty convincing my astronomy students that, from an observational point of view, cyclical time makes much more sense than linear time. I ask them to place themselves in the ancient world with no clocks or telescopes or computers, but only their senses to guide them and imagine what they would be capable of understanding about time. The days would be marked by the daily motions of the Sun and other celestial objects rising and setting in the sky, the months would be marked by repeated phases of the Moon, and the years would be marked by the reappearance of certain constellations in the sky. Other cycles in nature, such as the seasons, tides, menstrual cycles, birth-life-death, and the rise and fall of dynasties and civilizations, would dominate ancient life.

It should therefore be no surprise that the religion and worldview of many cultures were based on a belief in cyclical time. Among them were the Babylonians, ancient Chinese Buddhists, ancient Greeks and Romans, Native Americans, Aztecs, Mayans, and the Old Norse. These societies practiced an ancient astronomy called astrology which had as its chief function the charting of the motions of heavenly objects to predict where people were in some current cycle. It was a complicated process, because there are multiple cycles occurring in the heavens at any time, and ancient beliefs were based on the idea that human fate was determined by cycles working within other cycles. As a result, ancient calendars, such as the Hindu and Mayan, were very elaborate with a sophistication that surpasses those of the modern West. The idea of cyclical time continues in the present day with Hindu tradition and native European tradition such as that of the Sami people of northern Scandinavia.

Mayan calendar

Not only does cyclical time make sense in terms of what people observe in nature, but it also satisfies a deep emotional need for predictability and some degree of control over events that the idea of linear time can’t. If time flows inexorably in one direction, then people are helplessly pulled along, as though by a powerful river current, toward unpredictable events and inevitable death. Cyclical time gives the promise of eternal rebirth and renewal, just as spring always follows winter. These pagan beliefs were so powerful that they continue to influence all of us today; for example, the celebration of the belief in the constant process of renewal is the basis for the New Year holiday.

Obviously, all people have thought in terms of linear time on a daily level, otherwise they wouldn’t be able to function. But on the larger scale of months, years, and lifetimes, the notion of linear time was viewed as vulgar and irreverent. A cyclical view of time was a way for people to elevate themselves above the common and vulgar and become connected to that which appeared heavenly, eternal, and sacred. This view also offered a form of salvation in the hope that no matter how bad things are in the world at the moment, the world will inevitably return to some mythical ideal time and offer an escape from the terror of linear time. You and I would consider this ideal time to be in the past, but in cyclical cultures, the past, the present, and the future are one.

Primitive cultures, like the Australian aborigines, had no word for time in the abstract sense—that is, a concept of time that exists apart from people and the world. For them, time was concretely linked to events in their lives—the past, the present, and the future formed an indistinguishable whole as the great cycles determined everything. The ancient Hebrews also had no word for and therefore no concept of abstract time, yet their concept of time was a linear one in which events occurred sequentially. These events formed the basis for their concrete notion of time. Except for the first six days of creation, time as described in the Old Testament was completely tied to earthly events like seasons, harvest, and, most importantly, God’s interaction with the world.

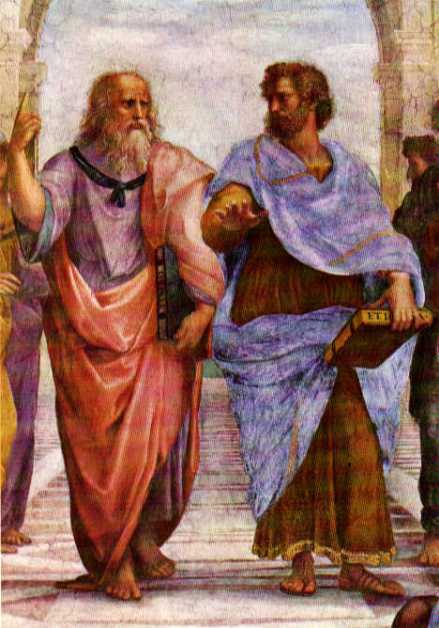

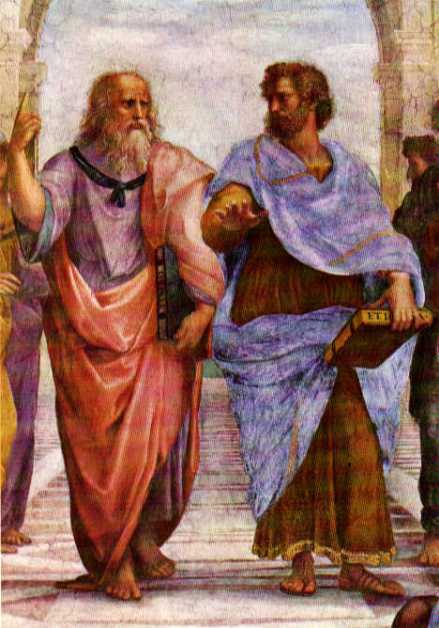

The ancient Greeks also believed the universe was cyclical in nature, but unlike other ancient cultures they also believed in an abstract notion of time that exists separately from events. They had two words for time—chronos and kairos—representing quantitative/sequential time and qualitative/non-sequential time respectively. From chronos we derive familiar time-related words such as chronological, chronic, and anachronism. In order to appreciate the Greek concept of time, one has to understand that to the Greeks time was motion. It’s not difficult to envision since the length of a day is measured by tracing the path of the sun and stars across the sky. When Plato spoke of time, he described an “image of eternity … moving according to number.” His student, Aristotle, said that time is “the number of motion in respect of before and after.”

Plato and Aristotle from the fresco “The School of Athens” by Raffaello (1510)

The Judeo-Christian beliefs about time that emerged during the time from Moses to that of Jesus mark a profound break with the thinking of the ancient past. Events of the Bible clearly indicate a unidirectional, sequential, notion of time that is utterly counter-intuitive to what the senses observe in nature. Time is not discussed directly in the Old Testament, but we can gain an understanding of the ancient Hebrew notion of time from the language. The ancient Hebrew root words for time were related to distance and direction: the root word for “past” and “east” (qedem, the direction of the rising Sun) is the same; the root word for the very far distant in time (olam), past or future, is also used for very far distant in space.

Perhaps the ancient Hebrews anticipated the early 20th century mathematician Hermann Minkowski, who postulated that space and time are two aspects of a single entity called spacetime. In any case, the Hebrew practice of viewing time from a perspective that looked backward was eventually adopted by modern astrophysics. The Judeo-Christian concept of linear time developed into our modern view of time and became one of the great foundations of modern science.

Something very powerful was required to overcome the ancient perceptions of and feelings about time. Though the concept of linear time started with Judaism, it took hold and was spread throughout the Western world by the rise of Christianity. In the fifth century, Augustine noted that the Bible is full of one-time events that do not recur, beginning with the creation of the universe, culminating with the Crucifixion and Resurrection, and ending with the Second Coming and Judgment Day. He realized that Christian time is therefore linear rather than cyclical. The desire for some sense of control and the hope for eternal renewal became better satisfied by a belief in a loving Creator and the resurrection of his Son who was sacrificed on the cross. (It is interesting to note, however, that cyclicality does have some place in Christianity—we are born when we leave the womb and we are reborn when we go to heaven.)

Nearly a thousand years after Augustine made his pronouncement, the era of clock time emerged. Clock time is measured by mechanical apparatuses rather than by natural events, and marks the final triumph of abstract linear time over concrete, cyclical, event-driven time. Mechanical clocks were invented in Europe in the 14th century, followed by spring-driven clocks in the 15th century. Refinements to spring-driven clocks in the 16th century enabled Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe to make his famously accurate celestial observations, which were used by Johannes Kepler to formulate the laws of planetary motion.

Tycho Brahe and his quadrant

However, the motivation for increasing precision in time-keeping was not motivated by pure science, but rather by the application of science in the quest for accurate navigation. Sea-faring navigators required precise measurements of time so that they could use the positions of star-patterns to determine longitude. With these highly precise clocks, it was possible to keep excellent time. It is interesting to note in the phrase “keeping time” the abstract notion, meaning we keep up with the external flow time rather than events defining the concrete notion of time.

It is not a coincidence that the era of modern science began after the invention of high-precision time-keeping devices. Modern science began with the Scientific Revolution in the 16th and 17th centuries, starting with the Copernican Revolution, but it progressed slowly because of a lack of necessary technology. Galileo, for instance, was forced to time some of his experiments by using his own heartbeat. By the late 17th century, Newton had formulated the branch of mathematics now referred to as calculus and published his laws of gravity and motion. His work was based on his belief in a flow of time that was both linear and absolute. Absolute time means that it always takes place at a rate that never changes.

Remember that the ancient Greeks viewed time and motion as one. This is important because the scientific study of motion based on the principle of cause and effect requires linear time. Newton’s laws and his view of time as absolute held sway for almost two hundred years. But Newton suffered from limited perspective just as the ancients had—humans perceive time on Earth as always taking place at the same rate, but that isn’t true. Newton is still considered the greatest scientist who ever lived, but we know now that he did not have the full picture.

Isaac Newton performing an experiment

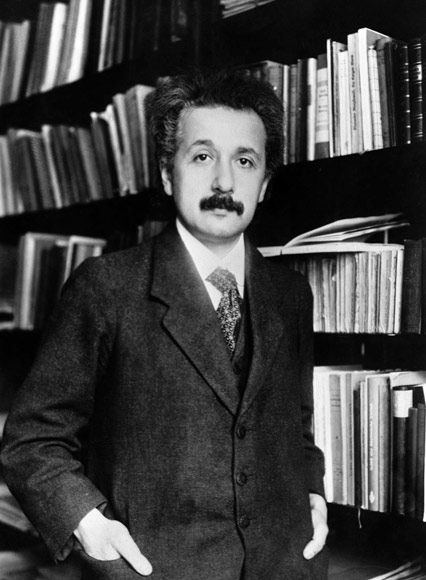

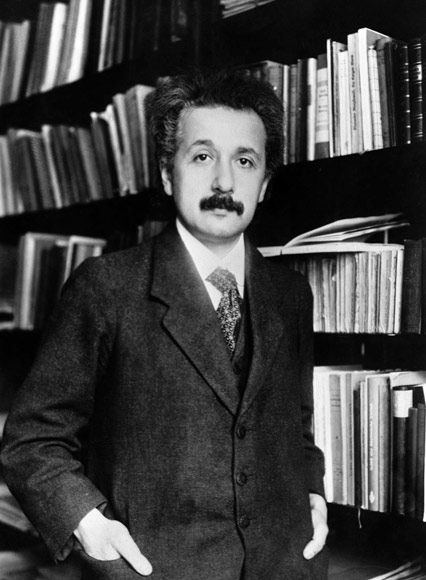

It was Albert Einstein and his theory of relativity that gave humankind the strange truth about time. By the early 20th century Einstein had succeeded in demolishing Newton’s notion of absolute time, showing instead that time is flexible, it goes by at a rate that is different in different places in the universe, and it is really dependent on the location and movement of the observer of time. It is interesting that the Bible anticipated this in Psalms 90:4, “For a thousand years in your sight are like a day that has just gone by, or like a watch in the night.”

The current scientific view of time is a combination of the ancient Greek abstract notion of time, the Judeo-Christian notion of linear time, and Einstein’s relative time. Cosmology, the branch of physics that deals with the overall structure and evolution of the universe, works with two times: local time, governed by the principles of relativity, and cosmic time, governed by the expansion of the universe. In local time, events occur in the medium of spacetime as opposed to being the cause of time. Time is motion, motion is time, and objects may freely move in any direction in space.

Albert Einstein

But the next big scientific question is, can objects also move in any direction in time? Physicists have determined that the arrow of time points in one direction. But how can we determine that direction? Biblically, we understand that time flows from the creation to Judgment Day. Scientifically, it has been less clear.

Ultimately, physicists determined that the arrow of time points in the direction of increasing disorder. A branch of physics known as thermodynamics, the study of how energy is converted into different forms, quantifies disorder using a concept called entropy. The second law of thermodynamics states that in a closed system, entropy (the amount of disorder) never decreases. This means the universe will never spontaneously move back in the direction of increasing order. It is the progression of the universe from order to disorder that provides the direction for the arrow of time.

The linearity and direction of time determined by thermodynamics seemed clear until physicist and mathematician Henri Poincaré showed mathematically that the second law of thermodynamics is not completely true. The Poincaré recurrence theorem proved that entropy could theoretically decrease spontaneously (the universe could go back in the direction of increased order). But, the timescale necessary to give this spontaneous decrease any significant chance of happening is so inconceivably long, much longer than the current age of the universe, there is little probability that it will happen before the universe could reach maximum entropy.

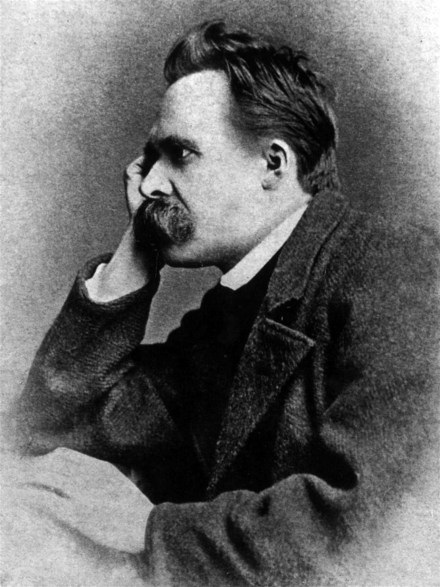

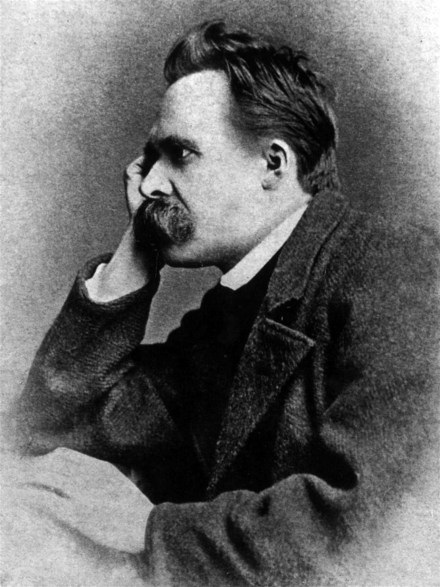

Nevertheless, some Western thinkers mistakenly took Poincaré’s theorem to mean that reality is cyclical in a way that does not provide the ancient escape from the profane to the sacred. This led these thinkers to despair about the possibility that human existence is nothing more than the pointless repetition of all events for all of eternity. Nineteenth century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche was one who took the Poincaré recurrence theorem to the hasty and illogical conclusion that there was no purpose or meaning to existence. On the other hand, there is little comfort to be gained from contemplating an endlessly expanding universe in which everything becomes hopelessly separated from everything else. One may well wonder if there is no escape from time.

Friedrich Nietzsche — contemplating the Poincaré recurrence theorem?

Christians need not despair. The Bible tells us that the universe in its present form will cease to exist on Judgment Day, which will presumably occur long before there is any significant probability of a Poincaré recurrence, and will certainly make the notion of an endless expansion moot. If that is true, we inhabit a universe that is for all purposes linear and finite in time, and we have a much happier fate than being condemned to a never-ending repetition of meaningless events or a universe that expands forever and ever.

While it is important that Christians understand that modern science confirms the biblical view of time, it is also important that Christians understand the role of biblical belief in shaping modern science. Modern science developed only after the biblical concept of linear time spread through the World as a result of Christianity. True science, which at its root is the study of cause and effect, absolutely requires linear time.

Fertile ground for modern science

The foundation of 21st century astronomy and physics is the big bang theory—the “orthodoxy of cosmology” as physicist Paul Davies describes it—which relies on linear time with a definite beginning. The false cyclical view was perpetuated by two human limitations: limited perspective and misleading emotions. It took faith in the Word of God enshrined in the Bible and trust in the scientific method to overcome these limitations so that humankind could understand the true nature of time.